"Tired of parties": voter turnout drops amid urban-rural enthusiasm gap

Malé turnout trails national average by 13 points as urban centres disengage.

Artwork: Dosain

30 Oct 2025, 18:17

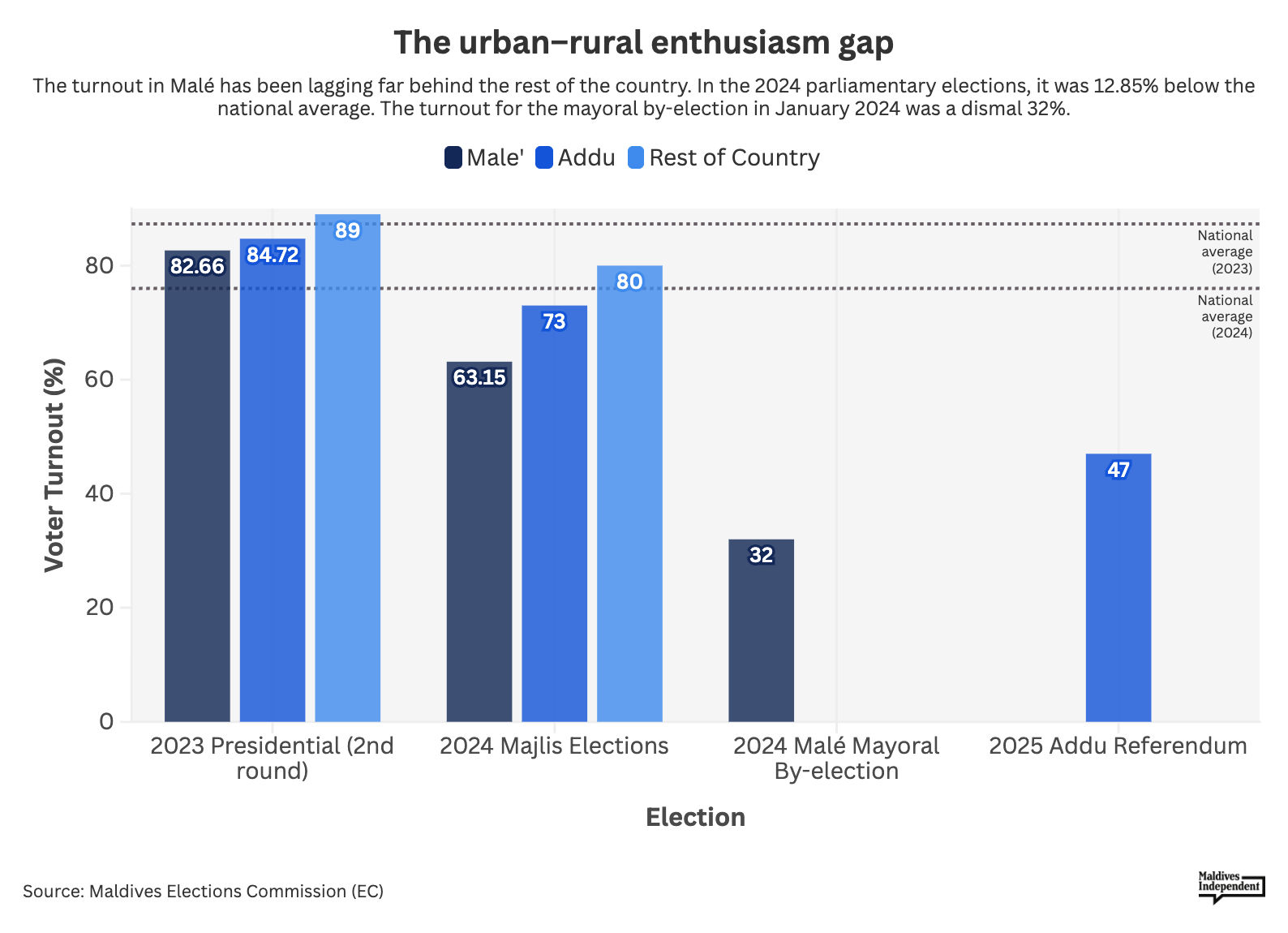

More than half of eligible voters stayed home when the future of Addu City's local government was on the ballot last Saturday. At a polling station in Malé, officials waited in near-empty rooms. The referendum question was settled decisively, but the evident lack of enthusiasm called the democratic process itself into question.

As the low turnout prompted concern and speculation on social media, Independent MP Abdul Rahman 'Ahdhu,' who campaigned for his Meedhoo constituency to break away from the Addu City Council, pushed back by pointing to the dismal turnout in Malé's mayoral by-election in January 2024.

"Malé Mayor Adam Azim was elected with 7,621 people voting out of 54,680 eligible voters. When Azim was elected as mayor with [the support of] 13 percent from the voting population, [only] 31 percent of eligible voters voted in this election," he observed.

Ahdhu blamed registration problems, difficulties with transport, and Addu voters residing in resorts and other islands with no polling stations. But the referendum outcome would have been the same "even if 100 percent of Addu Meedhoo's people had voted," he contended.

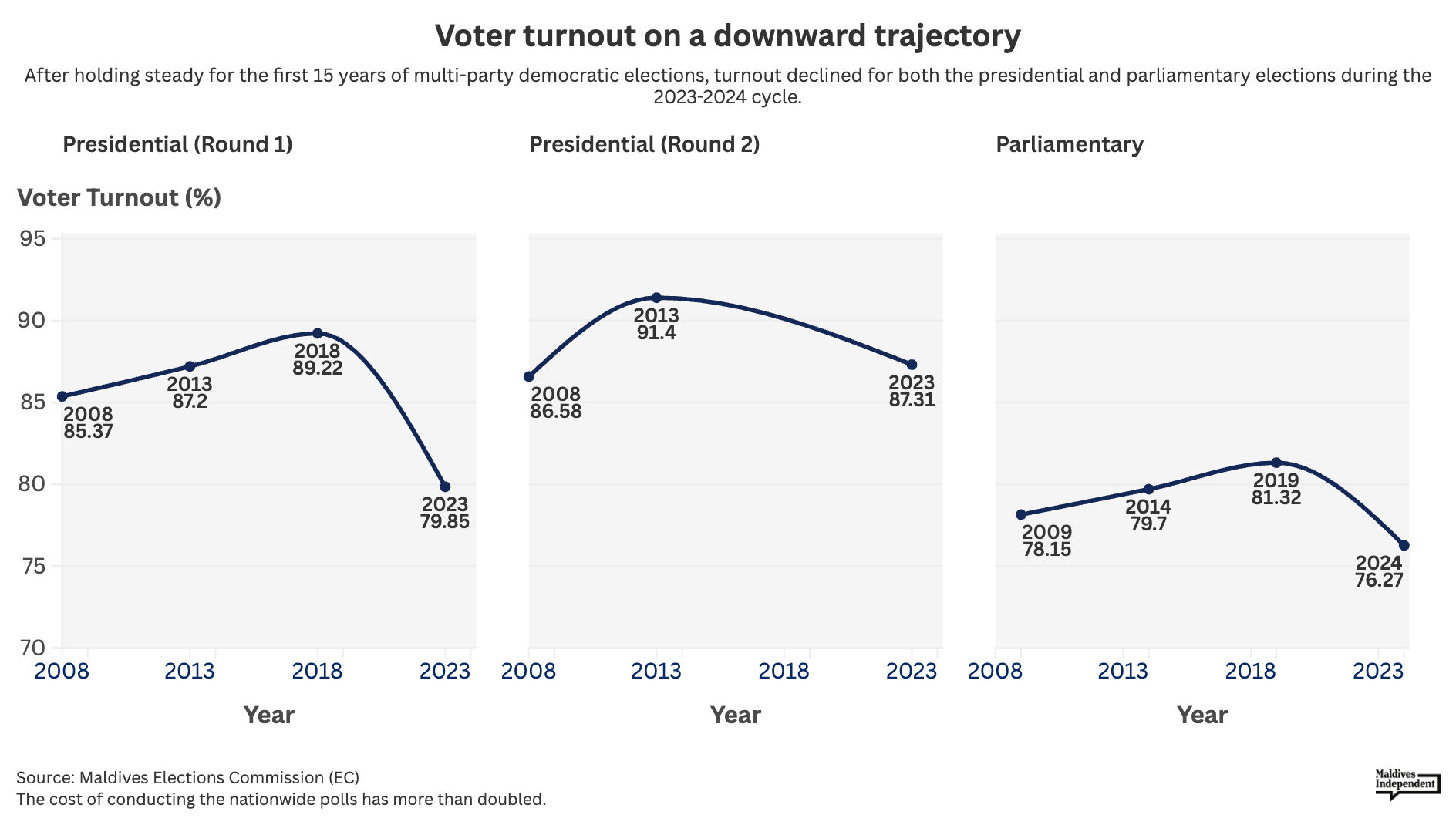

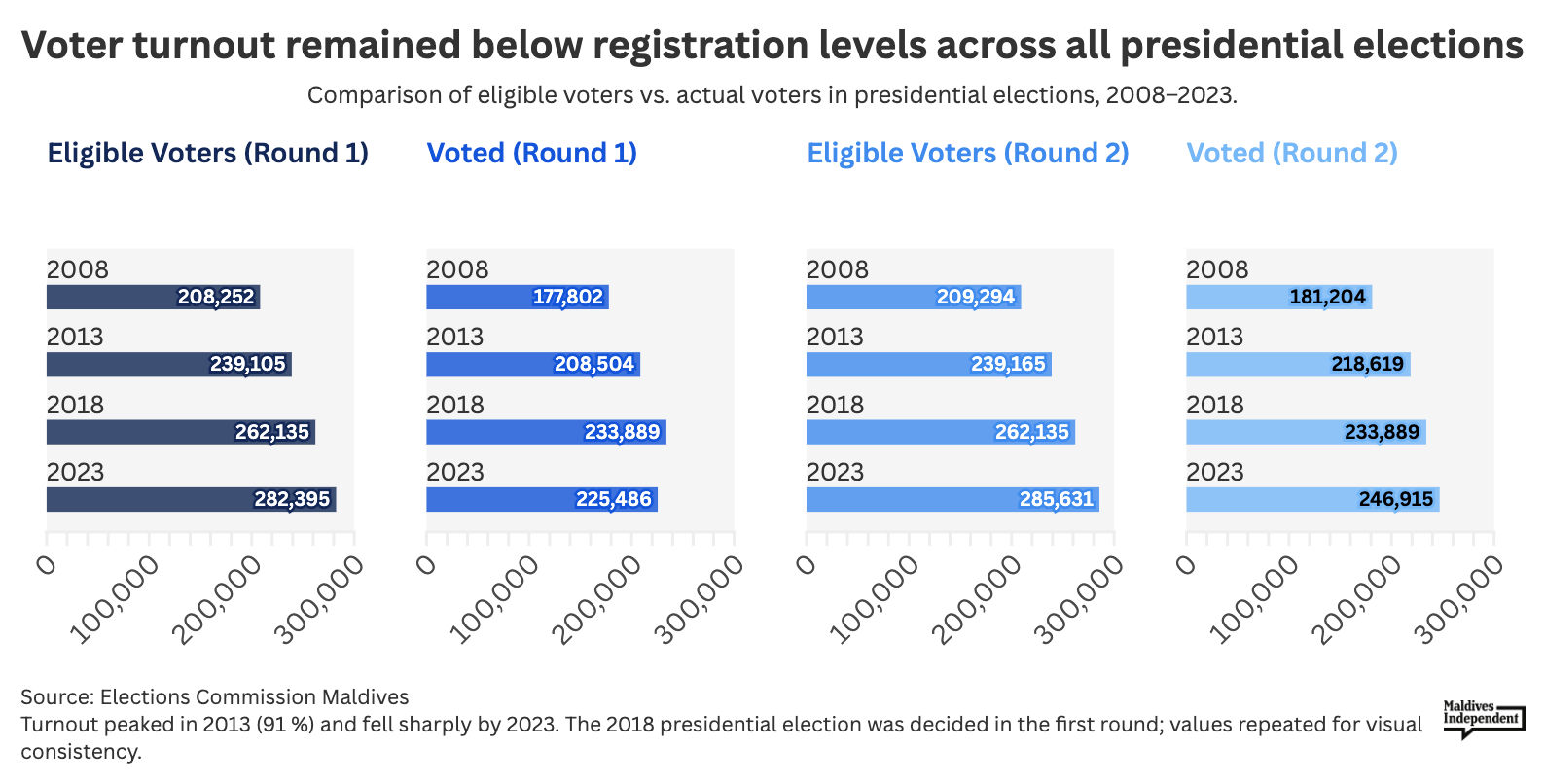

The low turnout in both cities reflects a troubling trend. Voter participation has been steadily declining since the country's first multi-party presidential election in 2008, registering the steepest fall in the 2024 parliamentary elections.

The presidential election turnout also dropped from a record high 91 percent in 2013 to 79 percent in the first round in 2023. In the run-off, invalid votes reached a record 7,888, including many who deliberately spoiled their ballots in protest.

The fall has not been uniform across geography or election type. Turnout remains relatively healthy in the atolls, but it has cratered in Malé and Addu – an urban-rural split that became more pronounced in the last election cycle.

When the current People's Majlis was elected in April 2024, Malé turnout was 12.85 percent below the national average of 76 percent. In a few boxes among the capital's constituencies, the turnout was below 50 percent. Addu trailed by a smaller margin of three percent below the overall figure. In contrast, turnout in the rest of the country (excluding Malé and Addu) was 80 percent – 4.6 percent above the national average.

A failing system

Voter apathy and disengagement in Malé have also been reflected in the low turnout for political rallies and demonstrations. The opposition Maldivian Democratic Party, which once drew massive crowds that filled the capital's street, has been struggling to bring out 100 people in a city home to 175,000 Maldivians.

MPs from both the ruling and opposition who spoke to the Maldives Independent diagnosed similar problems: a political party system marked by internal splits and broken promises, self-serving political leaders, and voters who have lost faith.

"People are very tired of the party system," said MP Abdulla Rifau from the ruling People's National Congress, who represents the Maafannu South constituency in Malé.

He referred to a breakaway faction weakening the MDP during the previous administration. “At the most crucial point, the MDP split. Again another party formed. And again that newly-formed party worked to not keep the MDP in power at any cost. So among them there will also be some who are fed up with it and don’t come out to vote,” he explained.

Rifau said it was normal for turnout to decline across presidential, parliamentary and local council elections with more people consistently voting in the former. Despite the downward trend, voter turnout has not reached a crisis point yet, he suggested, attributing the decline to the "failure" of the multi-party system as well as a lack of both trust and interest.

MDP MP Mauroof Zakir, who represents the Baa Kendhoo constituency, agreed that growing public distrust and disillusionment were key factors.

“Because manifestos are created, promises are made, they come to the elections, and after winning the election, the delivery isn’t very good – and this is true regardless of which ideology," he explained.

"Since things don’t work out that way, people become fed up with politics. So the decreasing hope that by voting they can achieve the outcome they want - that’s one problem that lowers [turnout]."

Mauroof – who is also president of the Maldives Trade Union Congress and general secretary of the Tourism Employees Association of Maldives – highlighted the purported absence of political ideologies in the country.

"Every human being naturally has some ideology inherently, whether they support the right or the left. However, political parties in the Maldives are not based on that,” he said.

The inability to choose a political party based on alignment with values keeps voters away, he suggested.

“For example, MDP says it’s a center-right political party, but works as center-left. Then the other parties don’t even self-define what ideology they want. So there are various mixed people in them. Therefore, it’s very difficult for ideology-driven policies to come from within. So what happens is there are mixed policies. That’s the second biggest reason for frustration,” Mauroof argued.

This problem is compounded by politicians pursuing self-interest or pushing thinly-veiled agendas. When elected officials fail to serve the public or hold the government accountable, "hope diminishes, hope is lost," he said.

"Because if voting won’t make things better, then what they hope for is to gain some temporary benefit from it. To gain it and finish that matter right there and people don’t expect anything better after the election whether they win or not," he said.

Showing up

Political scientists have explained declining turnout in established democracies through three interconnected forces: dealignment, as voters shed their traditional party loyalties; weakening party identification, as more citizens call themselves independents; and institutional distrust, driven by broken promises, corruption scandals, and a sense that voting doesn't change anything. When all three trends converge, democracies face what scholars call a "crisis of engagement."

The Maldives ruling party lawmaker stressed that change requires showing up to vote.

Rifau pointed out that the law does not set a minimum turnout threshold for an election to be valid. A candidate will be elected even if those who are unhappy with the system do not vote, he said.

“This is also something the public should think about,” he said.

Rifaau suggested that electoral reforms proposed by President Dr Mohamed Muizzu to introduce ranked choice voting and combine the presidential and parliamentary elections could boost turnout “as a majority of the people coming out will cast [their votes] before they leave.”

Both changes would require public approval in a referendum.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.