Green climate fund grants Maldives US$23m for safe water

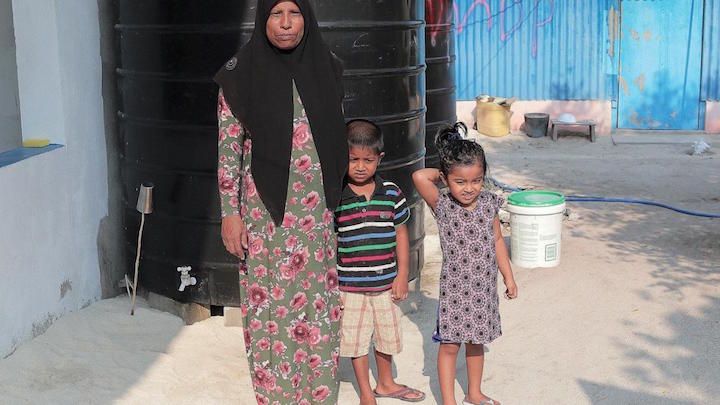

The UN’s climate fund has approved US$23.6 million for a project to ensure the delivery of safe freshwater to 105,000 people in the outer islands of the Maldives. The project is among the first eight investments approved by the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a global initiative established to provide financing from wealthy nations for adaptation projects in developing countries.

09 Nov 2015, 09:00

The Green Climate Fund has approved US$23.6 million for a project to ensure the delivery of safe freshwater to 105,000 people in the outer islands of the Maldives.

The project is among the first eight investments approved by the GCF, a global initiative established to provide financing from wealthy nations for adaptation projects in developing countries. The GCF has released US$183 million in funding ahead of crucial climate change talks in Paris.

The five-year adaptation project in the Maldives is due to begin on February 15, 2016 and aims to help vulnerable communities manage climate-change induced water shortages.

Several islands across the Maldives report water shortages during the dry season each year.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.