Two decades after the tsunami, "safer islands" need expansion and protection

Environmental groups warned this would happen within decades.

Artwork: Dosain

28 Dec 2025, 17:11

Oral histories suggest the ancestors of Raa Kandholhudhoo's fishing community once lived in Dhuvaafaru in the same atoll. Centuries after erosion forced them to abandon the island, their descendants returned as part of a "safer island" programme devised in the wake of the Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004.

Each year at 9:20am on December 26 – the moment the waves reached the Maldives – a minute of silence is observed nationwide. The tsunami's anniversary is marked annually as National Unity Day.

The 9.1-magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Sumatra at 6:58am local time. The tsunami reached the Maldives about three hours later, travelling at speeds of up to 750 kilometres per hour (faster than a commercial jet). Of the country's 199 inhabited islands, 190 were affected. The waves killed 82 people, left 26 missing, and displaced 15,000 people – a per-capita toll comparable to the worst-hit nations.

The devastation wiped out decades of development in a single day, costing the Maldives US$ 304 million or 35 percent of GDP.

Saltwater intrusion destroyed half of the country's cultivated land. Four islands – Kandholhudhoo, Madifushi, Gemendhoo, and Vilufushi – were permanently abandoned and 14 islands were evacuated in the immediate aftermath. More than 5,200 houses required repairs and 2,878 houses required full reconstruction.

On the 14 worst-affected islands, a quarter of vessels were damaged; one in six beyond repair. Four out of five school children lost books, uniforms or both. Two-thirds of women and more than half of men showed signs of moderate psychological distress six months later.

Bolstered by extensive international funding and support, former President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom's administration adopted a “build back better” or a “safer island” policy. It was explicitly aimed at becoming more resilient in the face of future climate shocks.

Twenty one years after the worst natural disaster in the country's history, we're looking at how two key islands have fared since the resettlement of some of the worst-affected communities.

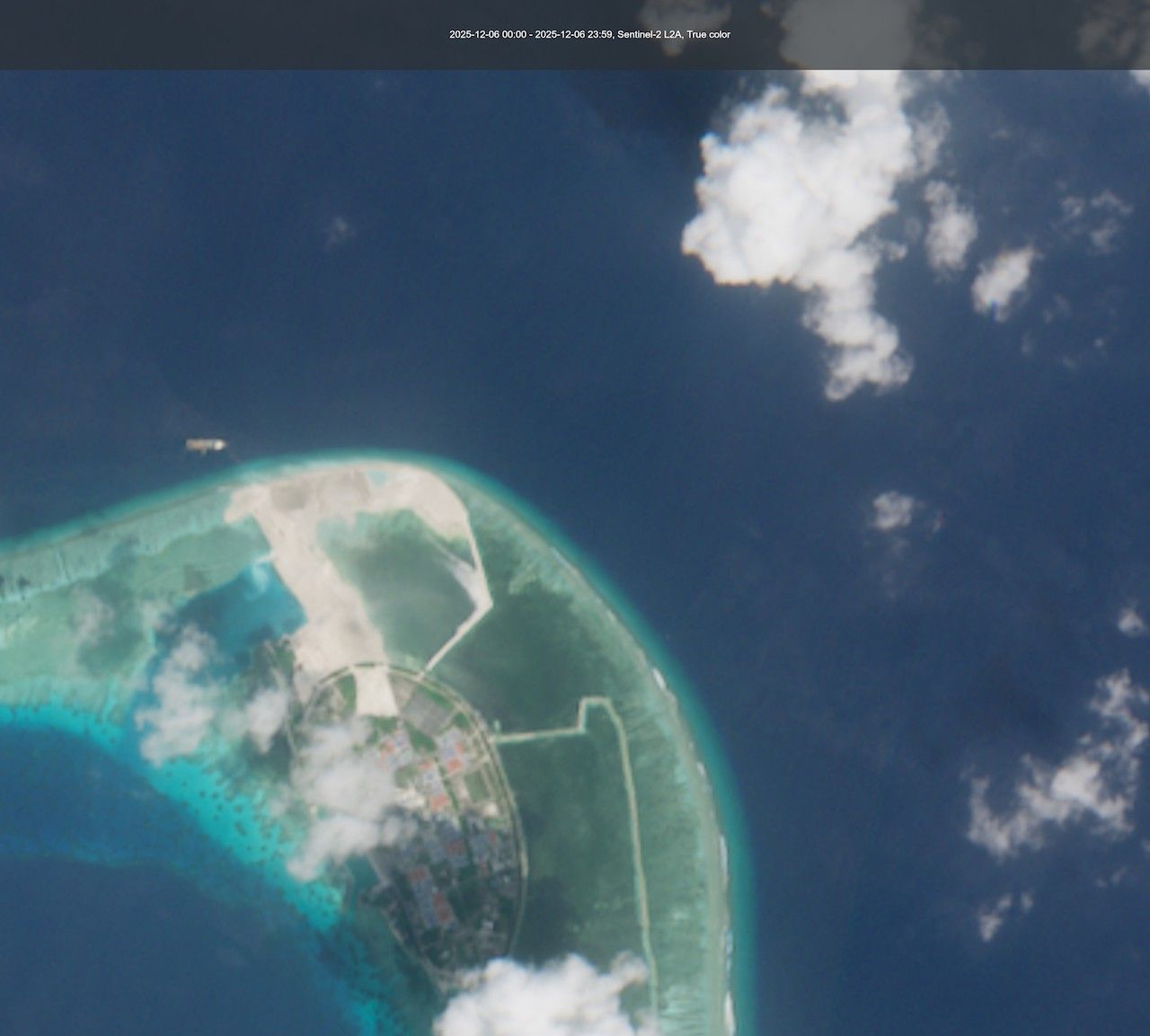

Dhuvaafaru

Dhuvaafaru, an uninhabited island at the time, was developed to relocate the displaced population of Kandholhudhoo. About 3,700 people had been scattered over five islands in Raa atoll after the tsunami destroyed their island and killed three people.

Since Kandholhudhoo had already been overcrowded before the tsunami, the government decided that reconstruction would not be feasible.

The displaced community was resettled in 2009. Developed under the “safer island concept," Dhuvaafaru’s plan included an Environmental Protection Zone of 87,218 square metres to be constructed at the outer edge of the island as well as elevated areas for public buildings intended for emergency evacuation.

The Dhuvaafaru project was described as the largest single post-tsunami reconstruction effort. It was one of the most ambitious projects undertaken by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. The IFRC’s Tsunami Recovery Programme funded the project at an estimated cost of US$ 42 million.

The project included 676 housing units, three schools, an auditorium, an administrative building as well as a sewage system, a mosque, health centre, power station and athletics facility. Lian Beng of Singapore and local contractor Amin Construction carried out the work.

There was opposition to Dhuvaafaru’s selection at the time. Local environmental NGO Bluepeace criticised the lack of community participation and questioned whether Dhuvaafaru could serve as a safer island due to its low elevation and dynamic, moving beaches. The group called it a “bad choice” for reconstruction as the island was too small for Kandholhudhoo’s projected population growth. Dhuvaaafaru would need additional land reclamation, which would make it more susceptible to flooding and erosion, Bluepeace warned.

“The people of Kandholhudhoo, after suffering from population congestion and land scarcity, would encounter the same problems within a few decades in Dhuvaafaru. Some government officials and even a few islanders seemed to envision a solution in the pristine lagoon of Dhuvaafaru. They were hoping to reclaim the lagoon and find new land, even though such an expansion would make the island even more vulnerable.”, the NGO said at the time.

The warning proved prescient and was borne out far sooner than predicted.

Despite the planning and development as a safer island, media reports from recent years suggest Dhuvaafaru has faced flooding during the rainy season. The contours of the island itself has also changed. In 2022, the state-owned Maldives Transport and Contracting Company completed reclamation of more than 22 hectares of new land – along with the construction of 424 metres of rock boulder revetment and 70 metres of breakwater – to address a “housing shortage.”

Ahead of their relocation in 2009, the people of Kandholhudhoo had also expressed reservations about Dhuvaafaru. Sixteen years later, several younger and older people continue to reminisce about their lost home. Some have even refused to renew ID cards to change their permanent address.

Vilufushi

The tsunami killed 18 people on the island of Vilufushi in Thaa atoll and completely displaced the population.

As former national university chancellor Dr Hassan Hameed explained, the tsunami waves amplified dramatically as they entered the shallower water off islands with large, shallow lagoons. Vilufushi was devastated in part because of its expansive lagoon. Fuvahmulah, which has almost no lagoon, escaped major damage. The damage in Malé could have been worse if so much of the capital's lagoon had not been reclaimed over the years, he noted.

Along with coastal protection, the reconstruction plan for VIlufushi included the reclamation of new land surrounding the island, tripling its size from 16 hectares to 61 hectares. The project was funded by the Netherlands government and carried out by Dutch company Boskalis. The island was also elevated by one metre.

When President Gayoom launched the reconstruction efforts in June 2006, he said the reconstruction would be geared towards building resilience.

As with Dhuvaafaru, Vilufushi was the recipient of significant international aid and support for reconstruction. The British Red Cross built houses. The German Red Cross rebuilt the health centre. Australian Aid supported housing and infrastructure development.

The island currently has designated evacuation points built on higher ground and it is prepared for emergencies, an island council member told the Maldives Independent. Aerial analysis of Vilufushi shows the planned nature of land use.

However, Vilufushi’s shape will also change soon. Land reclamation was launched in September to develop an airport with a 1,800-metre runway. The Maldives Airport Company Limited was contracted for the project.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.