20 Oct 2018, 09:00

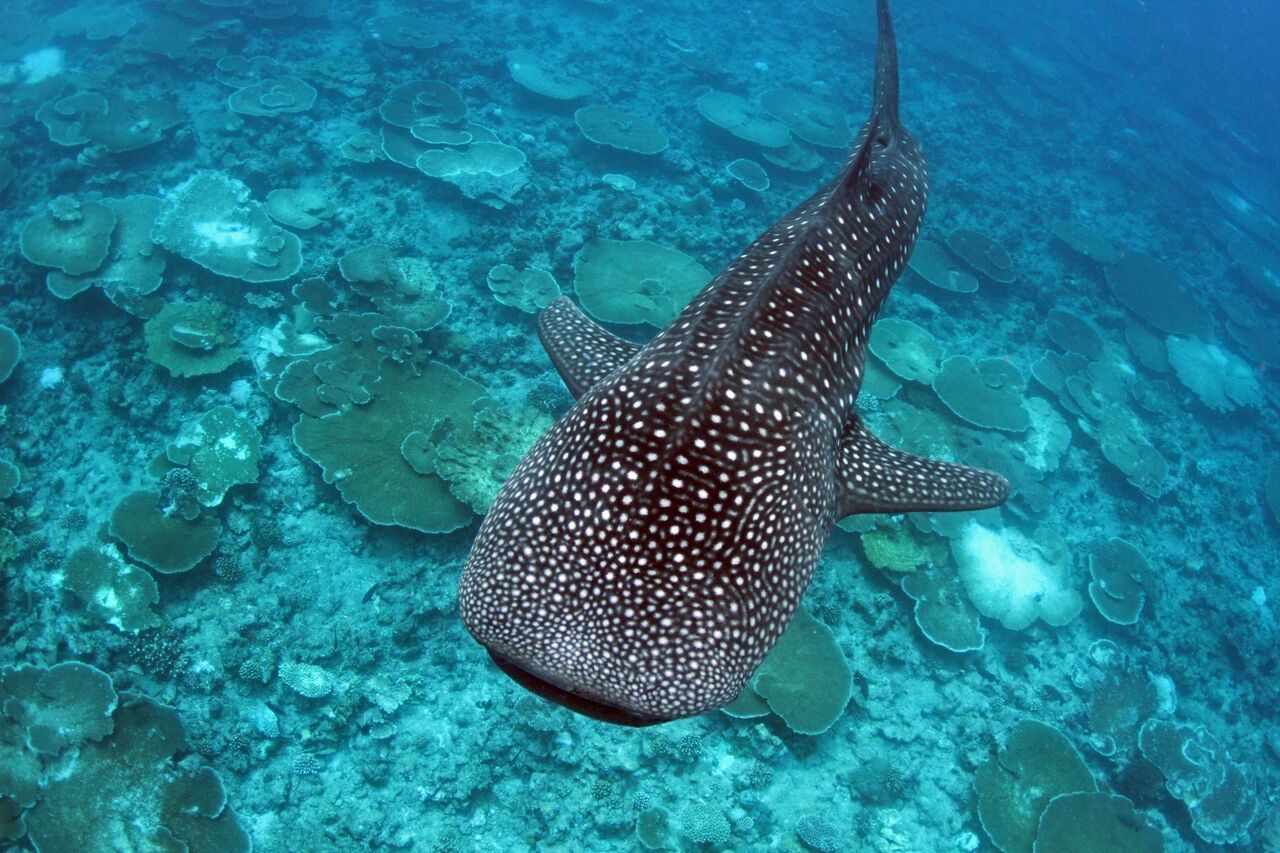

It’s a beautiful day with a cooling breeze and calm, crystal-clear waters underneath a dazzling blue sky.

I’m in a dhoni with six people. In the middle of the boat is our gear: masks, snorkels, ice box with drinks, and a bag full of snacks. We are well-stocked for a long day at sea.

From time to time we cross paths with other boats. European tourists, lazily sunning on deck, whizz past in speedboats. A dhoni passes full of Chinese tourists, geared up in snorkels, masks and life vests, ready to jump at a moment’s notice.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.