Life under for the life above

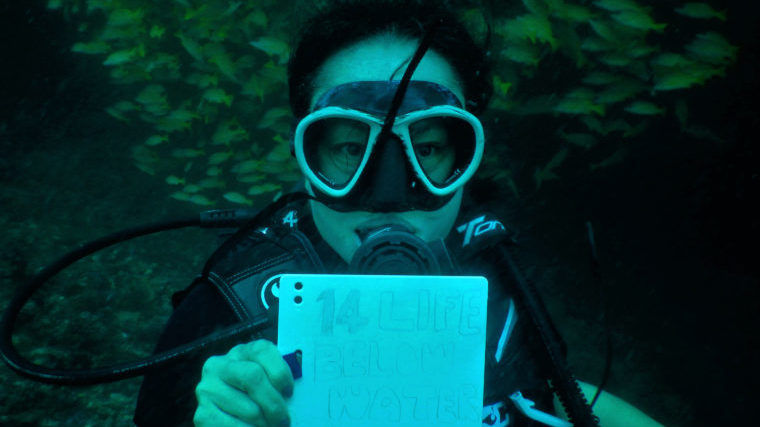

Shoko Noda, the UN resident coordinator to the Maldives, calls for the protection of marine life to be made the main focus of the country’s development plan

24 Oct 2016, 09:00

“It`s a country which is more sea than land. There, all men are rovers of the sea; all women, daughters of the waves” – The Maldives Islands, 1949

Squeezed in a subway in Tokyo one morning in 1992, I wondered how many fellow commuters had ever seen the magnificent underwater life. Only the previous day I had my first underwater diving experience witnessing incredible sea life – small and big fishes, swinging sea grass, and other life forms. The scene from the sea was in auto-loop in my head as I closed my eyes in an insanely crowded train that morning. I felt humble to be reminded that human beings occupied only 30 percent of the whole planet. The rest is covered with water, where a cosmos of its own exists.

As studies and work kept me busy in later years, I was deprived of diving opportunities. Since I joined the UN in 1998 I found myself repeatedly assigned in landlocked countries and capitals. I have seen raging mountainous rivers in Tajikistan, snow-covered Mongolian steppes, sky-penetrating Himalayan ranges, and barren Afghan-Pakistani border, but also have started to dream of blue oceans, white sand beaches, and all-year round tropical summer weather. And then in October 2014 I landed in the Maldives as the UN Resident Coordinator.

The beauty of the Maldives was irresistible. The incredible ocean ecosystem surrounding the Maldives awoke my long-hibernating diving bug. As my instructor gave a thumbs-down sign, I slowly sank down in the deep blue water—for the first time in more 20 years. Tropical fish under water look like a classic spring scene in Japan: pastel shade cherry blossoms whirling in the air. Mantas, turtles, sharks, or colorful powder blue surgeonfish and anemone fish all gracefully swum as if we, divers, did not exist. The 40 minutes diving took me back to the other universe that I once knew, and the humbling feeling I had in the subway in Tokyo came rushing back.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.