The US$ 500 million reckoning in April: what is a sukuk and why does it matter?

A guide to the Maldives' debt crunch in plain English.

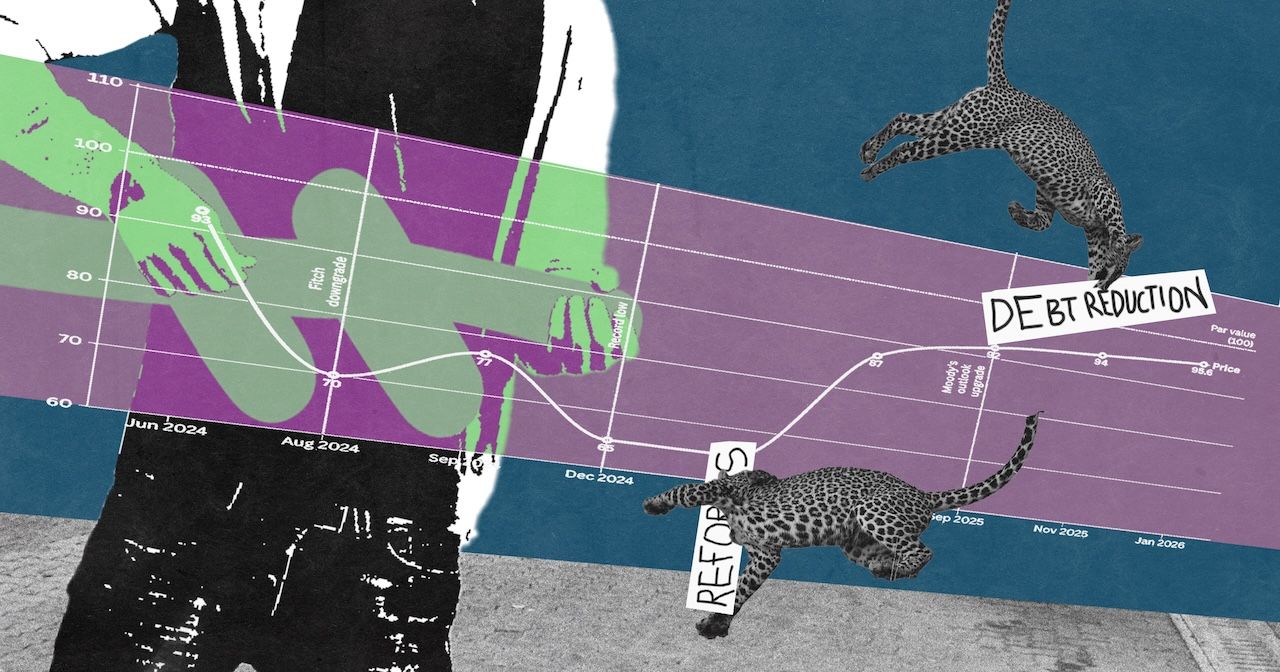

Artwork: Dosain

28 Jan, 16:21

What is a sukuk?

A sukuk is an Islamic financial certificate, essentially a bond that complies with sharia law. Traditional bonds pay interest, which is prohibited under Islamic finance principles. Sukuk get around this by giving investors partial ownership of a tangible asset. Instead of interest, investors receive a share of the returns generated by that asset.

A government or company creates a special purpose vehicle. This vehicle issues certificates to investors, uses the proceeds to purchase an asset from the originator, then leases it back. The lease payments flow through to investors as "profit" rather than interest. At maturity, the originator buys back the asset, returning the principal.

In practice, the payments work much like interest on a conventional bond. But the asset-backed structure makes it permissible under Islamic law and attractive to a global pool of Islamic investors.

How does the Maldives sukuk work?

Here's how it was structured:

Step 1: Create a special purpose vehicle

The government established a separate legal entity called Maldives Sukuk Issuance Limited in the Cayman Islands in February 2021. This SPV sits between the government and investors. Its purpose was to hold assets and channel payments.

Step 2: Issue certificates to investors

The SPV issued US$ 500 million in sukuk certificates across three tranches in 2021. Investors including pension funds, banks, hedge funds, asset managers from America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East bought the certificates. The September tranche was oversubscribed three times.

Step 3: Use the proceeds to buy an asset

The SPV used the US$ 500 million raised from investors to purchase an asset from the government: Dharumavantha hospital, a US$ 140 million government-run facility in Malé.

Step 4: Lease the asset back to the government

The SPV now technically owns the hospital. It leases it back to the government. The government pays rent to the SPV.

Step 5: Pay investors from the lease payments

The SPV channels the lease payments to sukuk holders as "profit" – not interest, which would violate Islamic law. The profit rate is 9.875 percent annually, paid every six months.

Step 6: At maturity, the government buys back the asset

On April 8, 2026, the government is supposed to repurchase the hospital from the SPV. The SPV then distributes that money, the $500 million principal, back to investors.

Why structure it this way?

The SPV serves as a protective buffer. Because it is a separate legal entity with its own assets and liabilities, it theoretically protects sukuk holders if the government runs into financial trouble. The asset-backed structure also makes sukuk sharia-compliant: investors earn returns from a tangible asset (the hospital lease) rather than from interest on a loan.

In theory, sukuk holders have a claim on Dharumavantha hospital as the underlying asset if the government defaults. However, in practice, no sovereign has ever defaulted on a sukuk, so the legal mechanics remain untested. Restructuring specialists call it "an opaque and poorly understood area of law."

Why did the Maldives issue the sukuk?

In 2021, the Maldives was reeling from Covid-19. When borders closed in March 2020, tourism – which accounts for about a quarter of GDP – came to a complete standstill. By mid-2021, arrivals had only recovered to 73 percent of 2019 levels. The budget deficit ballooned to 27.5 percent of GDP, far exceeding the approved target of 6.2 percent. Public debt climbed from 59 percent of GDP in 2019 to around 85 percent by 2021.

Starved of foreign currency, the government turned to Islamic capital markets.

How much is due in April?

Together with the final semi-annual profit payment and a separate US$ 100 million loan from the Abu Dhabi Fund that matures the same month, the total obligation approaches US $625 million.

But usable foreign currency reserves stood at US$ 197 million in November. The Sovereign Development Fund, which the government plans to tap for repayment, held US$ 126 million by the end of November.

Can the government pay?

Finance Minister Moosa Zameer says yes. "I can say with confidence that we now have the mechanism to be able to pay the sukuk in April," he told parliament in November. He outlined a plan to refinance US$ 350 million and repay US $150 million from the Sovereign Development Fund, which was to be built up with dollar revenue. The UAE has confirmed it will roll over the US$ 100 million Abu Dhabi Fund loan, he told lawmakers.

But Zameer has not disclosed the refinancing details, and Auditor General Hussain Niyazy – who has been briefed on "plan A, plan B, plan C" – says the information is "market sensitive." A fiscal policy expert who spoke to the Maldives Independent suggested the opacity was troubling: "It is unlikely that they can issue a sukuk or a bond in the next couple of months if they are not fully ready now. Or if they are planning to raise money from bilateral or multilateral sources, it should be committed already. No such details have been given."

What's the backup plan?

The government is reportedly negotiating a US$ 300 million loan from Cargill Financial Services International, an American commodities and financial services giant. The catch: the interest rate is said to be around 15 percent.

The Cargill loan is now close to being finalised, Adhadhu reported on Tuesday. The government is in the final stages of deciding whether to accept an interest rate above 14 percent, nearly double the 7.15 percent the previous administration paid for a loan from Cargill. The current administration previously guaranteed a US$ 50 million Cargill loan for the State Trading Organisation to import medicine, food staples, and essential goods, though the parliamentary finance committee meeting on that loan was held behind closed doors. Financial experts told the outlet that given the country's junk credit ratings, favourable terms are effectively off the table. The only realistic options are concessionary loans from states or multilateral institutions like the World Bank and IMF.

Bilateral support from Qatar and China appears in the budget tables, but it is unclear whether funds have been committed. India has provided crucial lifelines in the past – rolling over treasury bill subscriptions, extending a US$ 400 million currency swap, and providing rupee-denominated credit lines. But rupee financing does not directly solve a dollar-denominated obligation.

In the worst case, the government might scrape together enough from reserves and the Sovereign Development Fund to avoid default, the expert said. "But then the reserve will be drastically low and at dangerous levels. The parallel market rates for US dollars will increase significantly. Economic conditions will be difficult in the near-term, even though we escape a default."

What does the opposition say?

The Maldivian Democratic Party accused the government of failing to plan for an obligation it knew was coming. Former MDP chairman Fayyaz Ismail, a presidential hopeful, argued that refinancing sovereign debt is "a standard and prudent tool" and one the MDP government used successfully in 2021 when it issued the sukuk to refinance a US$ 250 million bond from the previous administration.

"This government came to power loudly attacking Covid-era debt, yet after more than two years in office, has delivered neither fiscal reform nor a credible plan for the sukuk it always knew was coming," Fayyaz wrote on X. "Instead, we are now witnessing complete silence."

He warned of a "dangerous scramble" that could lead to partial repayment undermining investor confidence, rushed private borrowing at undisclosed terms, and heavy depletion of reserves and the Sovereign Development Fund "just to get through April, leaving the country short of foreign currency, with almost no buffer to absorb shocks."

Fayyaz also raised concerns about unverified rumours of land sales to foreign countries, suggesting potential "threats to our sovereignty."

The MDP insists that borrowing during the pandemic was unavoidable. The administration had to plug a loss of more than MVR 25 billion in state revenue after tourism collapsed and revenue evaporated. "An economy over 65 percent dependent on tourism survived one of the worst global crises in modern history," the former economic development minister said.

In contrast, the current government inherited a recovering economy, rising revenues, and strong tourism growth, conditions under which debt should have fallen, Fayyaz said. Instead, borrowing has funded "political whims, from military drones to an ever-expanding list of political appointees," while small businesses crumble.

"The public deserves clear answers on the status of debt refinancing, and whether it is true that double-digit interest borrowing is now being pursued, making repayment even harder in the years ahead," he said.

What happens if the Maldives defaults?

No country has ever defaulted on a sovereign sukuk. Of the 22,794 Islamic bonds issued this century, only 62 have defaulted. All of those were corporate. A Maldives default would be a historic first.

The implications could ripple across Islamic finance. The unblemished sovereign record helps Muslim-majority countries borrow at better rates. In 2018, Gulf states bailed out Bahrain rather than let it become the first sovereign sukuk defaulter. A Maldives default could raise borrowing costs for others and undermine confidence in the sukuk instrument itself.

"The big question is now whether the Muslim countries will 'allow' Maldives to default on a sukuk bond," a Danske Bank portfolio manager told Bloomberg after the sukuk price hit record lows in September 2024.

How did we get here?

Successive governments borrowed to cover budget deficits rather than cutting spending. The sukuk was issued partly to settle about three-quarters of a US$ 250 million sovereign bond from 2017 that was maturing in 2022. It was essentially borrowing to repay borrowing.

At a parliamentary budget committee hearing in November, Auditor General Hussain Niyazy was blunt about the root cause: "We keep delaying and delaying every year. How far can we keep going and delaying? Cost-cutting has now become Satan's wedding. After delaying and delaying, it's not even written in the finance ministry's budget book now."

What's the total debt picture?

External debt repayments in 2026 are expected to exceed US$ 1 billion, more than 11 percent of GDP. Guaranteed debt, mainly borrowings by state-owned enterprises, stood at MVR 20.9 billion (US$ 1.3 billion) as of May 2025. Nearly 96 percent of that is denominated in foreign currency, adding to pressure on strained dollar reserves.

Is there any good news?

Markets appear cautiously optimistic. The sukuk price has recovered from a low of around 65 cents in late 2024 and April 2025 to over 96 cents, a sign that investors believe the government will find a way to pay. In late November, Moody's changed the outlook for the Maldives from negative to stable, citing improved reserves and strong tourism.

But Moody's also warned that the credit profile "remains constrained by very high debt levels, still sizeable external obligations due in the near term, as well as significant domestic refinancing needs."

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.