The US$ 500 million question: can the Maldives avoid default in April?

The 2021 sukuk comes home to roost.

Artwork: Dosain

15 Jan, 17:31

In less than three months, the Maldives government faces a moment of reckoning: repay US$ 500 million to international bondholders, or make history as the first nation to default on sovereign sukuk debt.

The Islamic bond was issued in 2021 at a punishing 9.875 percent profit rate. It comes due in April. Together with the final coupon payment and a US$ 100 million loan from the Abu Dhabi Fund that matures the same month, the total debt obligation in April could reach US$ 625 million – a sum that dwarfs usable foreign currency reserves that stood at US$ 197 million in November.

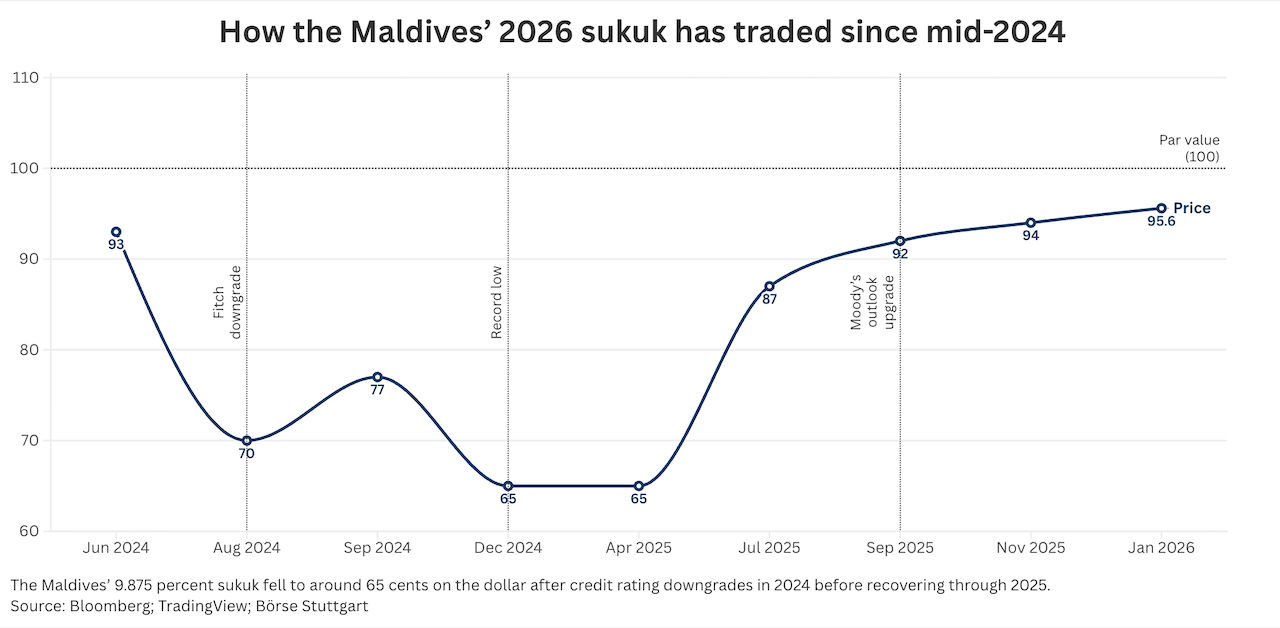

But Finance Minister Zameer has been projecting confidence. At a ceremony on January 5, he pointed to the dollar-denominated sukuk's market recovery as vindication of the government's approach, attributing the turnaround to "sincere work" by President Dr Mohamed Muizzu over the past two years, and contrasting it with the opposition's predictions of an imminent sovereign default since early 2024.

"If you look at our sukuk today, it's above 90," Zameer said. "The sukuk is very close to maturing. Its return has gone up by a lot. What I'm trying to say is that people are still buying with confidence. As you know, the sukuk had been sold then at a very high interest rate. So investors do have confidence."

The sukuk was trading at 95.6 cents on the dollar on Thursday – within striking distance of par (the 100-cent face value bondholders receive at maturity) – recovering from lows of around 70 cents in late 2024 and a record low of 65 cents in April 2025. The lows came when investors priced in a severe haircut after credit ratings agencies Fitch and Moody's downgraded the Maldives to "junk" status.

After double-digit losses in August 2024, the Fitch downgrade – citing “a rising degree of uncertainty” over the sukuk repayment – prompted a selloff as investors dumped the Islamic bonds. Bondholders were also spooked by an aborted move by the Bank of Maldives to impose restrictions on foreign currency transactions. In September 2024, Moody's echoed the assessment that “default risks have risen materially,” casting doubt over the government's ability to secure the "comprehensive financing to meet sizeable forthcoming maturities" as prohibitive rates ruled out international bond markets.

But the government has since made the biannual coupon payments on schedule and the sukuk price has stayed above 90 cents for the past five months.

At nearly 96 cents, an investor buying today stands to make roughly five percent in three months if the government pays in full (US$ 100 in addition to the final coupon for a US$ 96 outlay). A seller, however, prefers a guaranteed US$ 96 today over US$ 100 that might not arrive in April.

The premium reflects remaining uncertainty. But the current price "signifies that the market thinks that the government is not going to default, and that they will pay somehow," a fiscal policy expert explained to the Maldives Independent.

Unforgiving arithmetic

According to the 2026 budget's financing plan, the government plans to raise US$ 450 million from foreign sources, US$ 300 million as budget support from bilateral donors, and to withdraw US$ 272 million from the Sovereign Development Fund (SDF), which stood at US$ 126 million in November, according to Moody's.

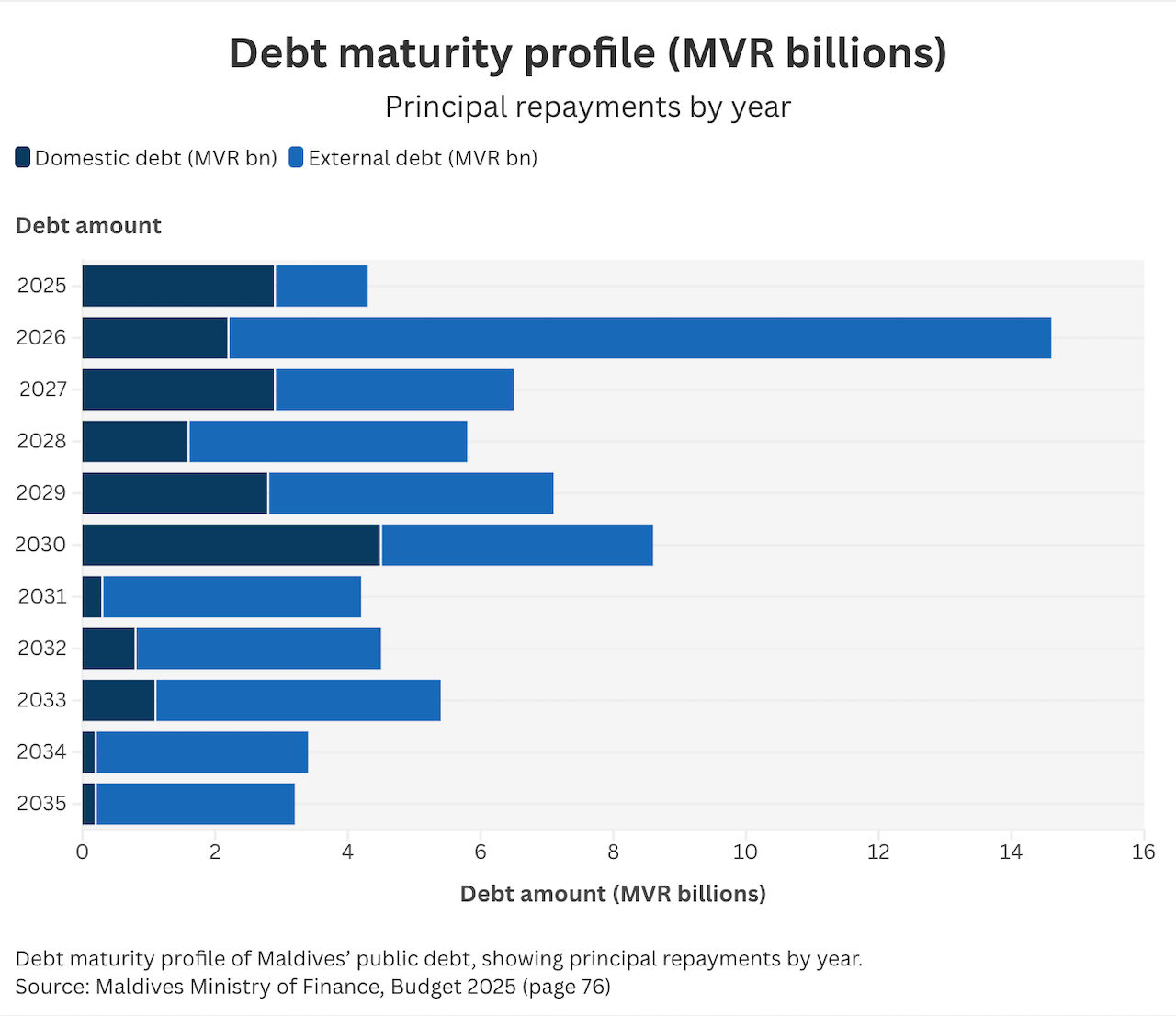

"I can say with confidence that we now have the mechanism to be able to pay the sukuk in April," Zameer told parliament's budget review committee on November 10. A week later, as MPs concluded the budget debate, he acknowledged that 2026 will be "the most difficult in terms of debt in the country's history."

At the budget committee, Zameer said the UAE had confirmed the rollover of the US$ 100 million bond after talks during President Muizzu's visit. For the sukuk, the government plans to refinance US$ 350 million and repay US$ 150 million by dipping into the SDF, which would be built up with dollar revenue. "That's how we've planned it. So we have confidence that we'll be able to solve this debt problem," he added, without disclosing any further details.

Zameer referred to a meeting with the auditor general on the previous day, during which the finance ministry "shared the efforts we've made to date, the correspondence, and additionally, our plan A, plan B, plan C."

Asked whether the government could obtain financing for debt repayment at favourable interest rates or whether loans would be taken at commercial rates, Auditor General Hussain Niyazy told the budget committee on November 9 that the finance ministry had shared estimates.

"However, a letter sent to us separately stated that it is market sensitive information. So it's a bit difficult for me at the moment for us to say something about that. But it would be good to ask that question of the finance minister. We have looked at their plan," he said.

The fiscal policy expert, a former top finance ministry official who spoke on the condition of anonymity, suggested the opacity was troubling.

"It is unlikely that they can issue a sukuk or a bond in the next couple of months if they are not fully ready now," he said this week. "Or if they are planning to raise money from bilateral or multilateral sources, it should be committed already. No such details have been given."

The price of Plan B

The government is in negotiations with Cargill Financial Services International, an American commodities and financial services giant, for a US$ 300 million loan, Adhadhu reported earlier this week. Cargill has offered financing, but at an interest rate so high the government has not yet accepted, sources told the outlet.

An account attributed to former President Mohamed Nasheed put the "predator lender" Cargill interest rate at 15 percent. For comparison, the previous administration borrowed US$ 100 million from Cargill at 7.15 percent. The current administration repaid that loan in March last year.

The source who spoke to the Maldives Independent said the Cargill loan might be conducted through a bank or a state-owned enterprise. "In either case, Cargill's rate will be double-digit, extremely high. This is not a sound plan and looks like a drastic measure where the government had failed with other alternatives," he said, blaming the lack of a sound fiscal policy and reform agenda, as a result of which "investors lack confidence in the Maldives economy in the medium term."

In the "worst case scenario" where the government is unable to secure external financing, it might be able to scrape together enough from the reserve and the SDF to avert default, the expert observed.

"But then the reserve will be drastically low and at dangerous levels. In this case, the parallel market rates [for US dollars] will increase significantly. Economic conditions will be difficult in the near-term in this case, even though we escape a default."

He assessed bilateral support to be a realistic possibility as the budget tables show "significant amounts from Qatar and China." But it is unclear whether the funds have been committed or secured. A fresh bond issuance was also "unlikely given the timing now and proximity to the maturity" exacerbated by global political uncertainties.

"Cargill seems to be a fall back option, but at a heavy cost," he said.

India has offered crucial lifelines in the past. The State Bank of India rolled over US$ 50 million in treasury bill subscriptions last year. A US$ 400 million currency swap with the Reserve Bank of India was extended before it expired in October. In June, India provided an additional US$ 565 million rupee-denominated credit line.

The government's exposure runs deeper than the sukuk. External debt repayments in 2026 are expected to exceed $1 billion – more than 11 percent of GDP.

"The primary risk confronting the state's debt portfolio is refinancing risk," a Fiscal Risk Statement accompanying the 2026 budget stated. Guaranteed debt, mainly borrowings by state-owned enterprises, stood at MVR 20.9 billion (US$ 1.3 billion) as of May 2025. Nearly 96 percent of that was denominated in foreign currency, adding to the pressure on dollar reserves.

The road to April

No sovereign has ever defaulted on a sukuk. Of the 22,794 Islamic bonds issued this century, only 62 have defaulted, all of which were corporate.

The Maldives sukuk was structured through a Cayman Islands special-purpose vehicle. The government-run US$ 140 million Dharumavantha hospital in Malé was listed as the underlying asset. In theory, sukuk holders have a claim on that asset. In practice, as restructuring specialists have noted, sovereign sukuk defaults remain "an opaque and poorly understood area of law."

“The big question is now whether the Muslim countries will ‘allow’ Maldives to default on a sukuk bond,” Soeren Moerch, a portfolio manager at Danske Bank, told Bloomberg after the sukuk price dropped to a record low.

In 2018, Gulf states bailed out Bahrain rather than let it become the first sovereign sukuk defaulter. The unblemished record helps Muslim-majority nations borrow at better rates. A Maldives default could raise costs for everyone and undermine confidence in the broader Islamic finance architecture.

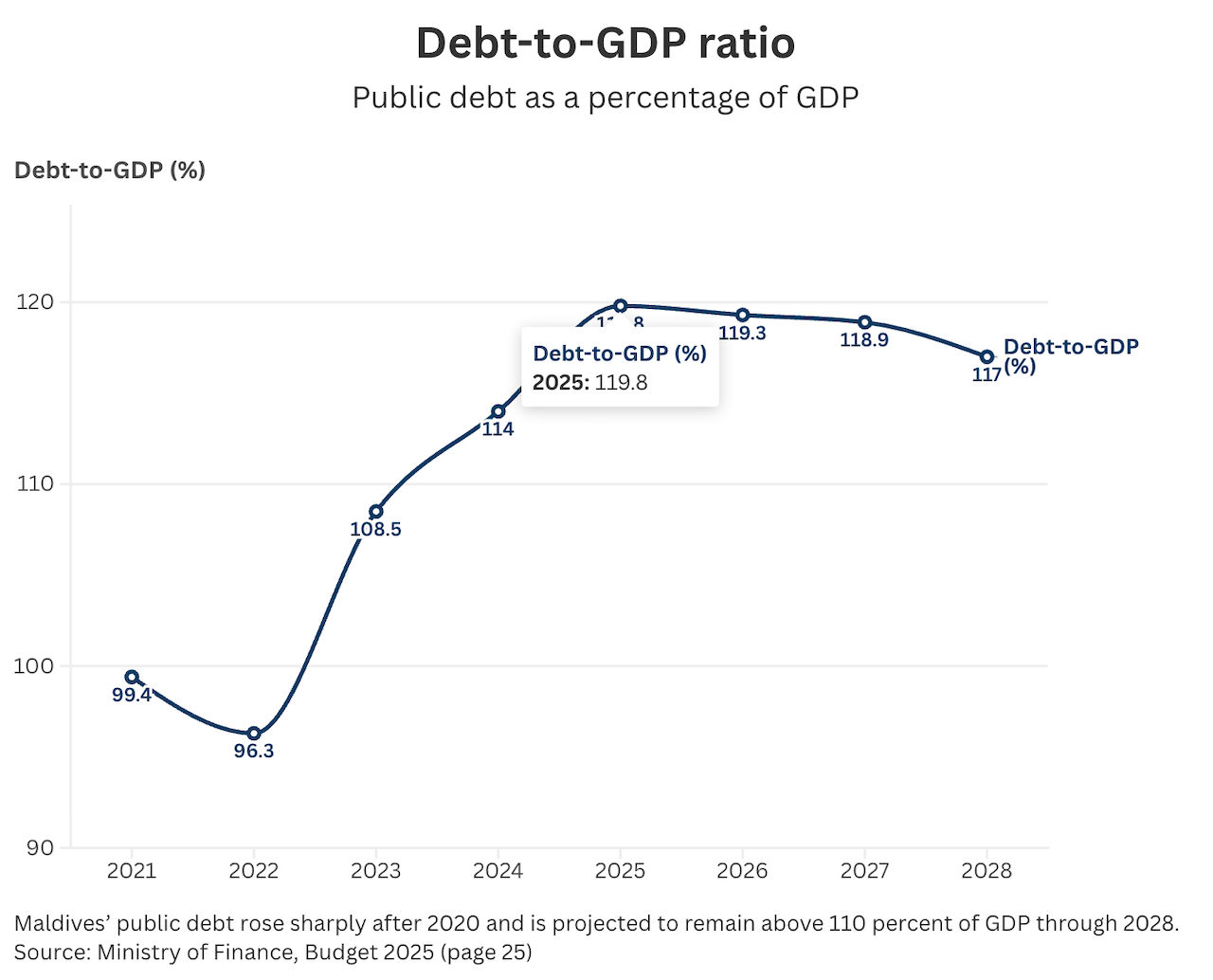

The sukuk was issued during the Maldives' recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021, former President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih's administration needed dollars and turned to Islamic capital markets, accepting a near-10 percent profit rate that reflected the country's risk profile. Over the bond's life, the government will have paid US$ 250 million in returns to investors. That is half the principal amount.

In late November, Moody's changed the outlook for the Maldives from negative to stable, reflecting its view that "external liquidity risks have eased from an elevated level as reforms to boost foreign currency receipts and robust tourism performance have bolstered the accumulation of external buffers".

The agency referred to a "track record of access to bilateral financing" as a positive sign.

"That said, Maldives' credit profile remain constrained by very high debt levels, still sizeable external obligations due in the near term as well as significant domestic refinancing needs," Moody's warned.

At the budget committee in November, Auditor General Niyazy was unequivocal on the root cause of the debt burden: the failure of successive administrations to reduce unsustainable government spending and borrowing to plug entrenched budget deficits.

"We keep delaying and delaying every year. How far can we keep going and delaying? Cost-cutting has now become satan's wedding. After delaying and delaying, it's not even written in the finance ministry's budget book now," he said.

"In other years, it's written in the budget book but not done. This year it's [it's not even there]. In one sense, as a principle, I think that's right. There's no point writing down something that's not going to be done. But how far can we keep putting this off?"

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.