Symbolic beginnings: Pest on rebellion, rhythm and responsibility

The Maldives’ most popular rapper talks literature, prison songs and why his music speaks for the marginalised.

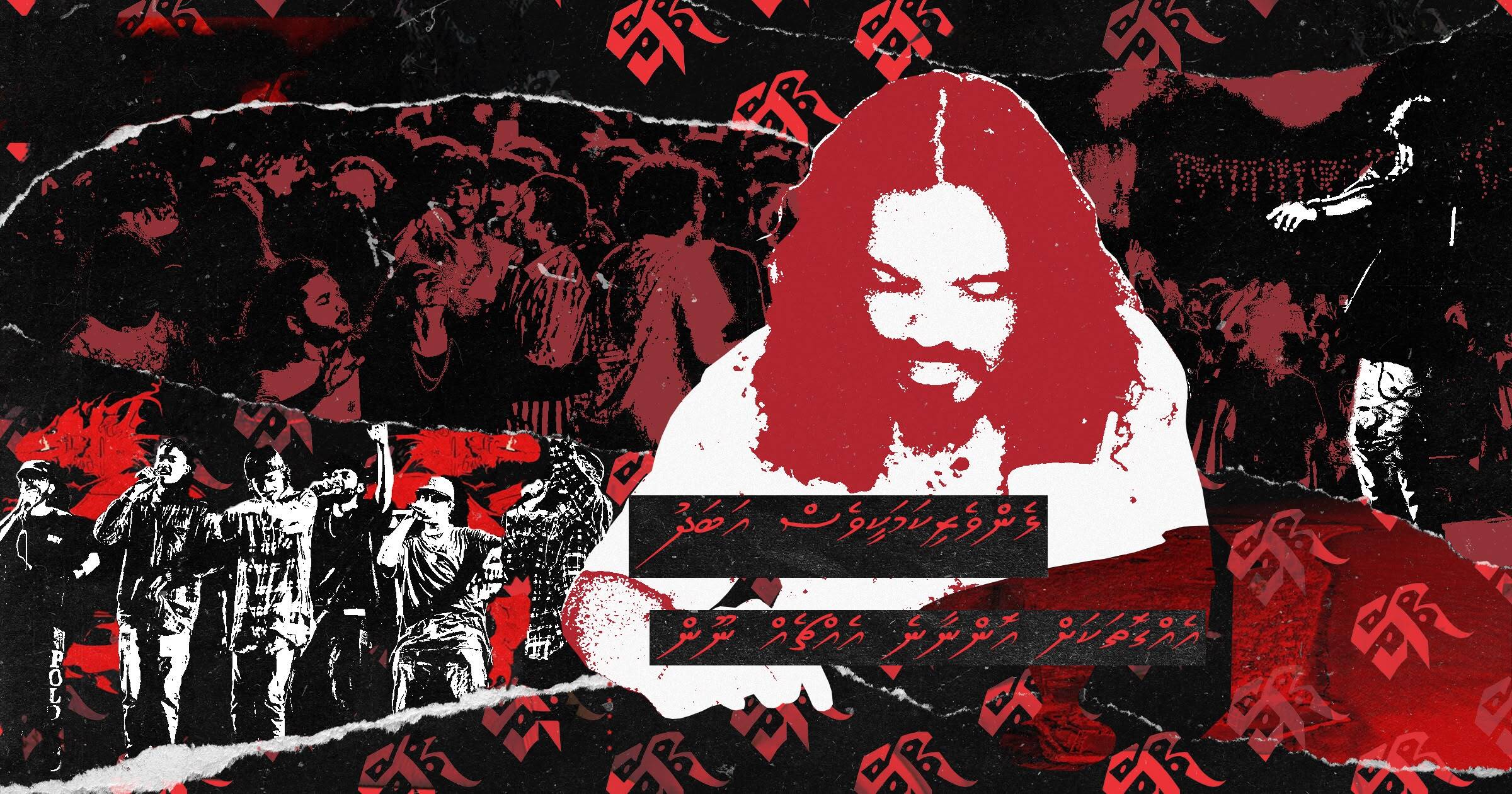

Artwork: Dosain

16 Aug 2025, 15:40

Hip-hop reared its head over our archipelago in 2011, a young genre attracting young talent. The most recognisable track from this period is without doubt Reethi Kudhin by Pest - a piece of the artist’s juvenilia that still gets plays. Not, it seems, to the artist’s pleasure – in fact, Pest’s journey can be seen as one that seeks to distance itself from that song.

No stranger to the stage even at a young age, Pest participated in Quran recitation competitions in his native Fuvahmulah. Things changed at a Scout Jamboree in Hulhumale’. For reasons he cannot recall, Pest was asked to perform a song, and he chose ‘Huttay Varey’.

“It was surprising to discover that I could sing,” says Pest, closing his eyes and running his fingers across his temples. “I mean, good enough for people to record my performance.” He wants me to know that it’s not simple vanity, but more the joy of discovering a gift within oneself.

Pest had not listened to much music at the time, preferring instead to read volumes of Dhivehi poetry. As there was little in the way of entertainment in his house, he watched Mendhurufas, a show on national television that featured Dhivehi songs. Cable TV was forbidden, and young Pest’s first introduction to hip-hop songwriting was via Eminem when he got access to a computer around 2004.

In that period, he was also exposed to Dhivehi Jalu Lava - prison songs - and Pest recalls being enthralled by them.

“They painted a very vivid picture of prison life,” he says. “Listening to those songs was like living in jail, they described the condition so well.”

The songs also relayed the everyday lives of people, including their living conditions in the capital, revealing many hardships in a world that wasn’t much talked about in the popular music of the day.

The prison songs were different from the songs on Mendhurufas. The latter were of a different style, heavy with metaphor whereas life in prison made the art of the incarcerated less subtle and layered, not at all poetic in the traditional Dhivehi sense. A major event for Pest was when he discovered a programme (on TV or radio - he can’t recall) that critiqued popular Dhivehi songs. It was hosted by two men, one of whom would poke fun mercilessly at awkward or nonsensical phrases, and another who’d offer constructive criticism.

Pest’s father was fond of music too, and his elder brother was also a well-known singer of devotional songs (Madaha) during his school days. Their father, who worked at the airport in Male’, bought a surround sound system. Pest got into a random African hip-hop album he found around the house, which proved to be a turning point. That was when Pest began to think seriously on the possibility of Dhivehi hip-hop.

Encouraged by Jalu Lava and inspired by a few lines of poetry in one of Bey’s notebooks, Pest tried his hand at songwriting, moving on to rap while in his mid-teens. It was around this time that he co-wrote his hit Reethi Kudhin with Edil. It became a proper song after Pest met rapper/producer Yes-e. Together with beatmaker Misty, they recorded Reethi Kudhin in early 2011. However, Pest didn’t get to enjoy the success of the song – he left for Mysore, India for studies soon after.

The Symbolic connection

‘Symbolic’ as a name has a curious history in Pest’s life. It was firstly the name of a group formed by Pest, Edil, Bey and some friends during their O’Level years in Fuvahmulah.

“It was more to do with rebellion. We made flyers, graffitied walls, made funny videos that Edil edited,” recalls Pest. Symbolic also included boys of different and rival wards (avah) in Fuvamulah, who found a greater unity within this order. Soon there was conflict with people who weren’t part of Symbolic, and suddenly, members of the group realised they needed help from the men of their avah.

“It became unsustainable,” explains Pest. He wanted to live in Male’ after he finished school, but his mother wouldn’t allow it unless he passed all his subjects. At the time, Pest’s grades had taken a nosedive, and he had to apply himself to get passing grades.

Pest had some relatives from Male’ and was close to his maternal cousins who lived in the capital with whom he often stayed. He was in touch with his Male’ relatives over Mig33, an instant messaging app popular among young Maldivians in the 2000s.

“‘Pestinba’ was my nickname on Mig33,” says Pest, revealing the origins of his hip-hop pseudonym.

After moving to Male’, on a trip to celebrate New Year’s Eve of 2010, he met two members of the Darknezz crew, a collective that was instrumental in the success of Pest’s breakthrough record. Later, he met with the group’s charismatic leader Eydee, a person with whom Pest would have a long-lasting working relationship. Eydee, Pest and the rest would meet and hang out at a famous café, Echcheh Kalheh, in ‘Campus Goalhi’, to enjoy their five rufiyaa YeYe coffees.

With Eydee, Bey, Edil and others, Pest finally co-founded Symbolic Records. The name was chosen partly because of how the original Symbolic group was forced to fold in school. They decided to breathe new life into the name from their teens.

Pest’s first album, Magumathi, was born from a desire to be more than Reethi Kudhin. When he returned from India, people called out the song’s title to him on the streets, and Pest felt pigeonholed. Using the Darknezz’s network, Pest and co. sent the Magumathi CDs to the islands, growing the fanbase organically. The album was a success and proved that Pest was more than a one-hit wonder. He was now an artist in his own right.

Pest’s songwriting has compelling elements, even his debut record. With Magey Vaahaka (My Story), he narrates a fable-like story about a lonely princess in a palace where Pest’s character becomes a servant just so he may gaze on her beauty. Eventually, he runs off with her, putting their lives at risk. It’s a very youthful, romantic Pest that we hear and though not the most inspired, the track has a certain aura. With Gini, though, the flow is tighter, the hook sinks deeper. The penultimate track Dhebandhihaaru has a tom-heavy beat and Zazu’s wavy vocals in the chorus are reminiscent of raivaru and patriotic songs. The rap on that track is fast, the rhymes seem effortless. On these tracks, you clearly sense a precursor to the older artist.

Lessons from Mysore and the lost years

As a young adult, Pest realised that he understood people very little, and this motivated his decision to study psychology on his own in Mysore. He also ventured into NLP (neuro-linguistic programming), an approach to personal development and psychotherapy that is now considered pseudoscientific. Armed with this and like Eminem before him, Pest sought to create a rapper’s persona.

“I experienced the fringes of society,” he says. “My songs occupy the space of the most disadvantaged among us. Those are the experiences I bring to the stage.”

Around 2014, Pest turned towards God and abandoned music, including his company Symbolic Records. Yet during this period of about three years, he continued to study poetry, enrolling in the Dhivehi Bahuge Academy’s poetry course.

“There’s a rich literary landscape here but it has almost no impact on the general public,” says Pest, recalling his time at the Academy. “I wanted to make something impactful and speak a language that the average listener can understand. I wanted to bridge this gap.”

Pest does not want to dwell on this period but at the end of it, the rapper returned to a changed landscape – CDs were dead, Edil had left. But, having released big hits such as Ihusaasthakey Mee, Hae Hae, Kuru Vaahaka, and several others, Symbolic Records was bigger than ever.

Present Day, L2

In the time between 2014 and the present Pest has released a handful of successful singles. These include 2018’s slow, contemplative Oyaa, his trippy collaboration with Aerth on Heylaa, the acerbic Koavareh, and 2022’s Veringe Verikan, an anthem about the privileges of those who govern versus the lot of the governed. Former President Mohamed Solih read the song’s lyrics at an MDP rally in 2024, much to Pest’s amusement, as the track was written and released while the Solih administration was in power.

His latest album, L2, was released this year. The production is polished, sophisticated. The opener Karudhaasthah Matheegaa has a simple syncopated drumbeat that propels Pest’s description of a mundane school day. In G-lyf though, the beat is powerful and an abrasive, fuzzy synth snakes into the hook and begins scratching like a DJ. The album’s most played track (on Spotify) is Ey Malaa, which Pest sings with female lead Isra. Its twangy guitars hover over drums that are painstakingly programmed, sounding almost live. My favourite though is the quieter Visnaalevey, which brings Pest’s vocals to the centre with its minimalism, and the stabs of synthesizers are stunning when paired with the sensuousness of Pest’s voice.

“Sanchu produced most of the album,” he says. “I don’t understand music theory, it’s all played by ear. If it sounds good, it’s good. I have a general sense of how I want a song to be, and I communicate that to Sanchu and the other producers. That’s my contribution, musically.”

Pest found inspiration in artists like Kanye, A$AP Rocky, even Billie Eilish, though he claims not to listen to music too much. People introduce music to him, he says, and the music they listen to adds to their character. He is also fond of the 20th century English poet Ezra Pound. Pound, Pest believes, was on a similar journey, exploring the nature of poetry and using a single sentence to speak volumes.

“[L2]’s not my best lyrically, I didn’t set out to do that,” he says. “I wanted the album to sound harmonious, I didn’t want the lyrics to overpower the music or the other way around.”

Lyrically, he deals with familiar themes on L2 – gangs, toxic relationships, desire. Despite what Pest says, there are some striking, evocative lines scattered throughout this album. Such as these from the opening track: Gasthahves kudavaahen gahuga nethas aibeh/visnun ve bonsai sikundeega moolaa [Translation: As plants become small but without defect, thought becomes bonsai and the brain grows roots].” Thought becoming bonsai is a piece of lyrical wizardry, extremely evocative, capturing how a mind can become stunted, not realising its full potential, denied growth by forces beyond its control.

But he ends on a high note where the album’s main character finds love and spiritual freedom. It is almost impossible to believe that this is the work of the same artist who wrote and sang Reethi Kudhin. But let’s not be too harsh - he was only sixteen.

On a cool night we visit the Gallery 350 where Pest examines work by Maldives and Chicago-based artists. He inspects each piece for some time before moving on. He seems most intrigued by the work of Moosa Mamduh, flipping carefully through the pages of his exhibit, a journal with asemic writing. Once he has viewed everything, we step out into the night air.

“It’s very different to the kind of art we normally encounter,” he says. “It’s good that there’s space for this now.”

“What’s next?” I ask him.

“Financial independence,” says Pest, wisely. That the Maldives’ most popular rapper isn’t yet financially independent is surprising. But then, that’s how artists often are. It takes a while for the emotions to quieten and the calm, methodical work of the devil to begin.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.