Does the Maldives practice what it preaches globally on human rights?

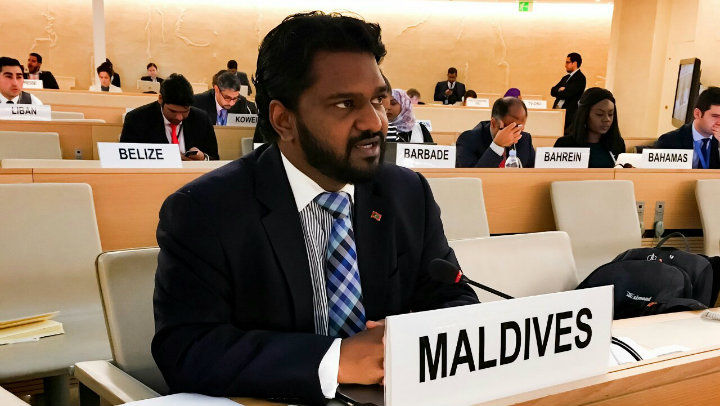

Jeffrey Salim Waheed takes questions on why the Maldives has sponsored several UN resolutions on freedom of expression and assembly, and judicial independence, despite practising the opposite at home

04 Oct 2016, 9:00 AM

Since its election to the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2010, the Maldives has been one of its most active members. Despite authoritarian reversals at home, the Maldives has advocated for human rights, sponsoring several resolutions on freedom of expression and assembly, and judicial independence.

In June, the Maldives was one of the main sponsors of a resolution urging states to ensure independence of judges and lawyers and impartiality of prosecutors.

The move came amid widespread condemnation of politicisation of the judiciary, following the jailing of key political figures, including former President Mohamed Nasheed.

The Maldives also sponsored a resolution on freedom of assembly and association in June, calling on states to assist special rapporteur Maina Kiai in expanding such freedoms globally, notwithstanding the fact that the Maldives itself had failed to respond to communications from Kiai.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.