Has the Maldives United Opposition failed to ‘restore democracy’?

As rumours of Yameen’s imminent ouster fizzle out and detainees languish in jail, Omkar Khandekar asks if the opposition coalition has failed in its bid to remove the embattled president and “restore democracy.”

02 Oct 2016, 09:00

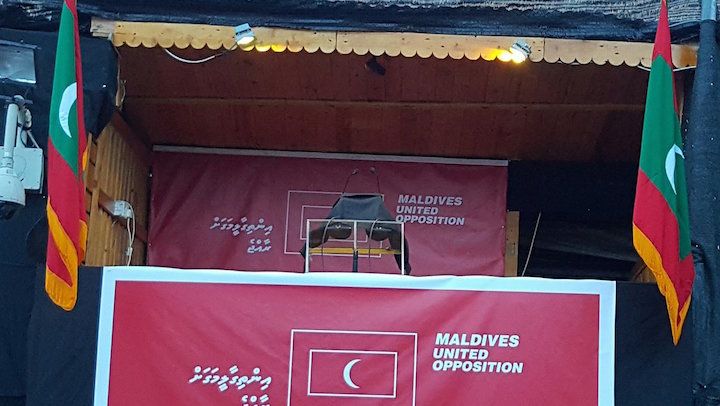

On a hot June night, Ahmed Mahloof sat at a dimly lit café by a beach, carefully coating a betel leaf with lime and pan masala. Four years ago, the MP led a series of anti-government rallies that eventually led to the resignation of the then-President Mohamed Nasheed. Now, as the newly appointed spokesperson of the Maldives United Opposition, he discussed plans to ensure the downfall of the government he had helped come to power.

“I really hope it takes two months,” he said. “Whatever we do, we should do it in two months.”

Mahloof is now serving a 10-month prison sentence for two counts of ‘obstructing police duty’. He isn’t the only one. Over the past three months, the police have arrested and interrogated several members of the opposition. Some had their mobile phones taken away, others were jailed for ‘plotting to overthrow the government’. Arrest warrants were issued against the MUO’s leaders, Nasheed and former Vice President Mohamed Jameel who now live in exile in the United Kingdom.

In September, as rumours of President Abdulla Yameen’s ouster started to fizzle out, Nasheed finally admitted to shortcomings in his plans. “There are a number of things that have to happen and we are working on them,” he told The Indian Express on concluding a brief trip to Sri Lanka, one that was said to have been part of a plot to oust Yameen.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.