One in six Maldivian teenagers has considered suicide. They're turning to AI for help.

Youth mental health consultations up 400 percent. The system can't cope.

Artwork: Dosain

15 Dec 2025, 16:00

Last Wednesday, more than one million Australian teenagers woke up to find their social media accounts deactivated. Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, Snapchat, YouTube, X, Reddit, Kick, Threads and Twitch were all gone, wiped clean under the world's first national ban on social media for under-16s.

With effect on December 10, the law requires platforms to take "reasonable steps" to prevent minors from creating or maintaining accounts. Fines of up to A$ 49.5 million (US$ 32 million) could be imposed for non-compliance. Children and parents face no penalties.

Other countries from Denmark to Malaysia could soon follow Australia's lead. The regulatory push comes amid a global debate about technology and adolescent mental health, one that has been shaped significantly by Jonathan Haidt's best-selling 2024 book The Anxious Generation. The American social psychologist argues that the shift to "phone-based childhood" around 2010 has driven an international surge in teen anxiety, depression, and self-harm. Australia's Prime Minister Anthony Albanese – who wants young people to "spend more time on the footy field" than glued to screens – has cited the book's prognosis in defending the ban.

But as policymakers around the world watch Australia's experiment unfold, a new report from the Maldives offers a more complicated picture.

Launched on the same day that Australia's social media ban came into force, the “Access and Experiences of Care: Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the Maldives” report suggests restricting digital access without building alternatives could leave vulnerable young people with nowhere to turn.

The digital crutch

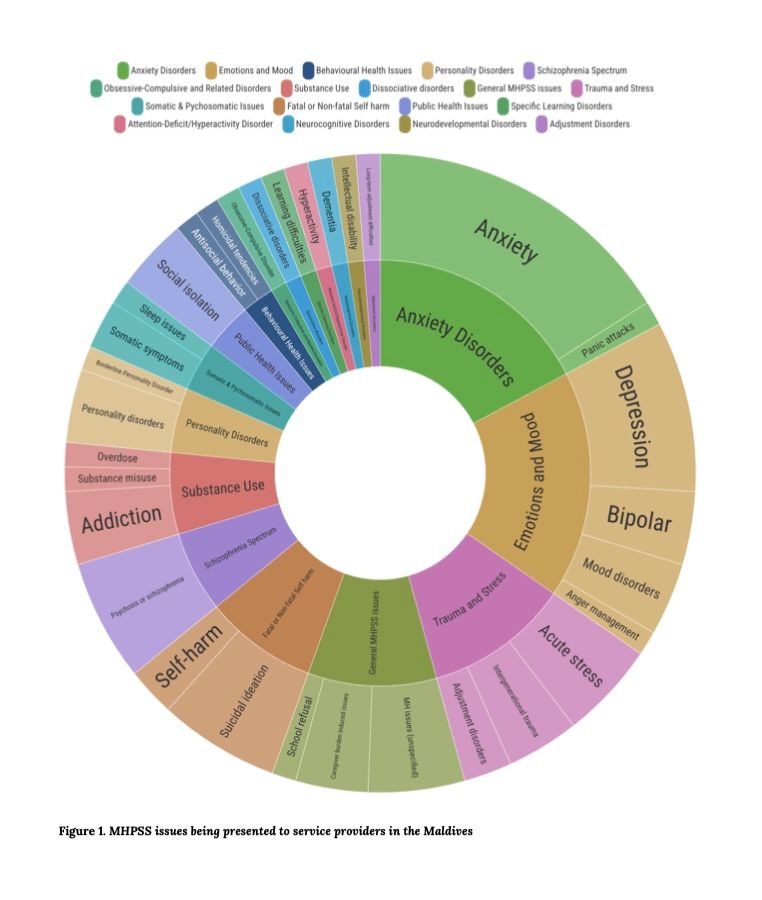

The Asia Foundation and the Maldivian Nurses Association published their findings after conducting one of the first nationwide qualitative studies of mental health services in the Maldives. Researchers spoke with 127 participants, service providers and service seekers, across 13 atolls.

The statistics are alarming. Among young people aged 13 to 15, about one in six had seriously considered suicide in the past year. Around one in seven had survived a suicide attempt. Roughly three in 10 Maldivians overall are estimated to experience mental health challenges.

But what caught the researchers' attention was not just the scale of the crisis but how young people were responding to it.

"As self-care practices and skills were not commonly known or taught, this had led many individuals to turn to AI or online sources for private, immediate support," the report found. It described this as "an unsafe option in the long term," noting the pattern was "especially the case for persons with disabilities and youth."

One service seeker explained the appeal: "AI systems are a private chatbot, so there is no fear of leaking. It's 24/7 available. It gives good answers that are easy for you to digest and make sense." Another youth participant echoed this use of AI for support: "We usually ask friends or check online what kind of help we need or we can get. We can type anything online these days and get answers from different AI systems as well as social media."

The report acknowledged that AI can be a "helpful complement for information, reflection prompts, or preparing questions for a clinician," but it is "not a substitute for human care and may actually cause harm in the longer term."

Recommended public health messaging included advising users to "avoid discussing specific methods of self-harm or suicide with AI, to set time limits for chats, to step away if they feel worse, and to seek immediate support if they notice increased distress."

A system under strain

The report documented a mental health system that is overwhelmed, centralised, and largely inaccessible to those who need it most.

Some service providers reported waiting lists of 60 to 100 people. The National Mental Health hotline received more than 12,000 calls over two years. These numbers continue to grow. Specialised services are concentrated in Malé, leaving other islands with significant gaps, and schools have "unmanageable student-to-counsellor ratios."

The result is a system geared toward crisis response rather than prevention. "When capacity is thin, practice skews toward reactive, treatment-oriented care: people are engaged late, and responses focus on emergencies," the report found. "Over time, this normalises the idea that care is short, urgent, and about problem-containment… rather than also including ongoing, relational support such as screening, psychoeducation, skills building, and follow-up." One provider put it simply: "Patients only come here in a crisis state."

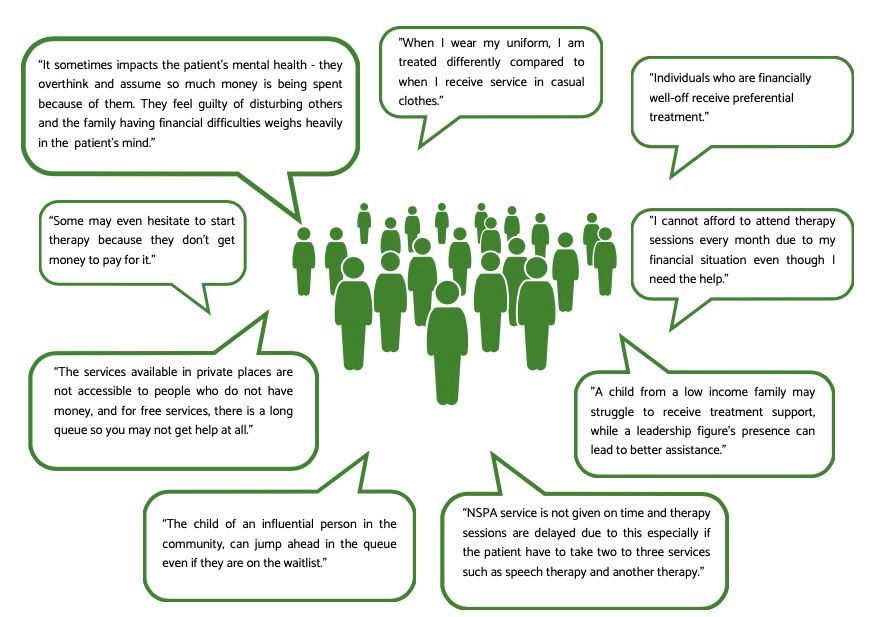

Then there is the stigma. In small and close-knit island communities, seeking help can trigger gossip, ostracism, and reputational damage. One service provider told researchers: "When you go to school counsellors to seek help, others consider it shameful, labelled as possessed by ghosts."

Confidentiality breaches compound the problem. "If you are from a poor family, confidentiality leaks quickly," one service seeker said. Another noted: "It's hard to open up when you don't know how they will talk about you later."

The cost of accessing care is also prohibitive. Therapy sessions can run from MVR 550 (US$ 36) to MVR 15,000. Medication can cost up to MVR 7,000. For patients who do not reside in the capital, travel and accommodation for a single care episode can add MVR 25,000 to MVR 50,000. One service user told researchers: "I spent 50,000 MVR in just 20 days. I just couldn't continue."

Last month, President Dr Mohamed Muizzu announced that the government health insurance scheme Aasandha will "fully cover all mental health expenses from 1 January 2026."

The numbers behind the crisis

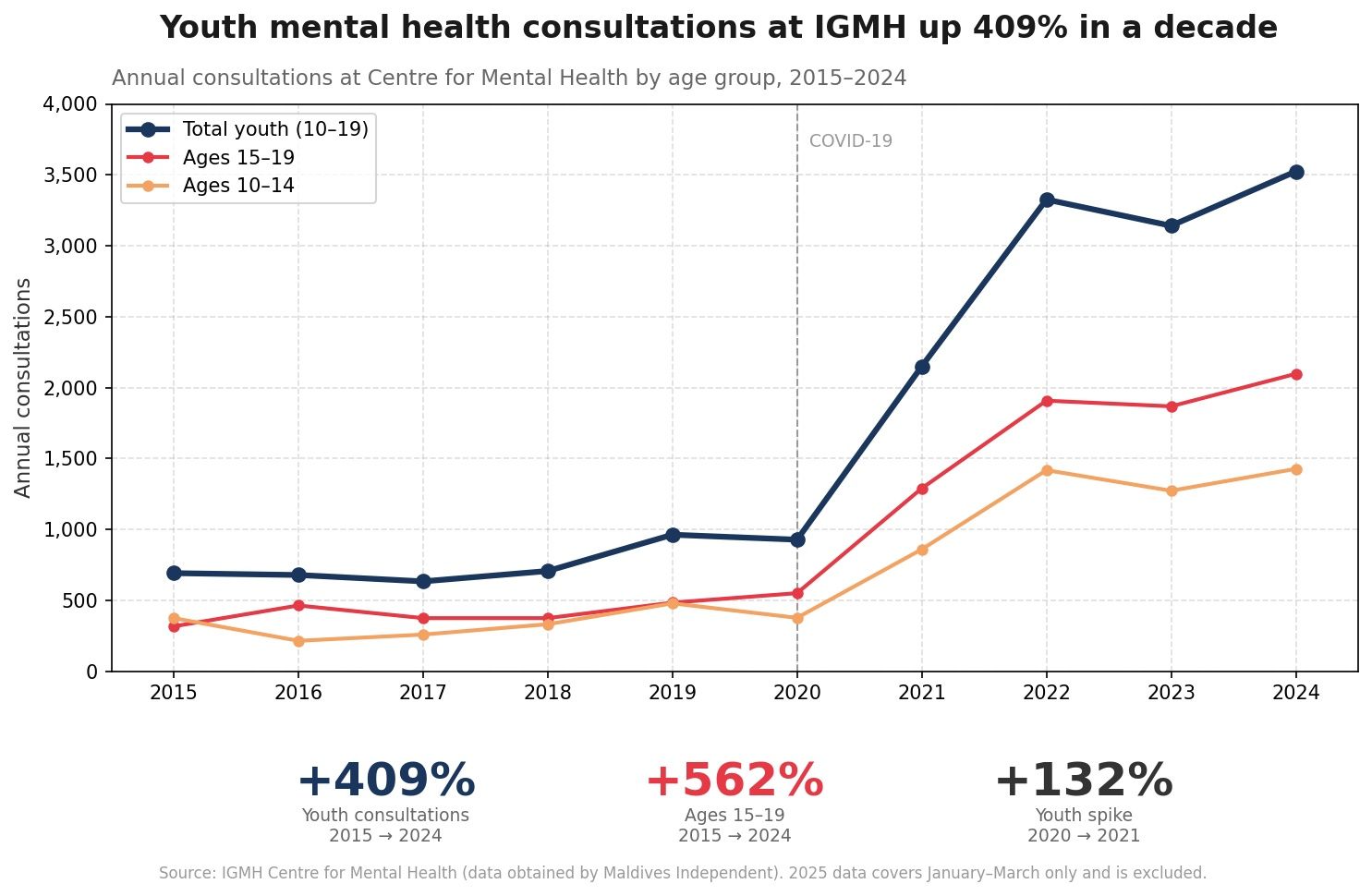

Data obtained by the Maldives Independent from the government-run Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital shows the scale of what providers are facing. Youth mental health consultations for patients aged 10 to 19 increased by more than 400 percent or roughly fivefold between 2015 and 2024.

In 2015, the centre recorded 692 consultations for this age group. That figure reached 3,524 by 2024. The sharpest rise was among 15 to 19 year olds, where consultations increased by 562 percent over the same period.

The data shows a clear inflection point around 2021, when youth consultations more than doubled in a single year. This could reflect both the mental health impact of the Covid-19 lockdowns and increased willingness to seek help. But the numbers have not returned to pre-pandemic levels. 2024 was the peak year on record.

Young people now account for nearly one in five of all mental health consultations at the centre, up from around one in eight a decade ago.

"People don't know how to deal with these kinds of things"

The report captures a generation caught between inadequate professional support and well-meaning but often unhelpful family responses.

"Our parents, our grandparents, instead of asking what happened, they will say go pray," one young service seeker told researchers.

Service providers observed that "people only learn about the disorders that are popular online." Misinformation fills the vacuum when accurate information and support are unavailable. One provider articulated the gap: "We need parenting support, how to talk to children, how to manage devices, how to raise them well."

A young person described the consequences of self-managing without guidance: "Most people will do something by themselves; we have seen [the] condition going from bad to worse because people don't know how to deal with these kinds of things."

Instead of medication or clinical intervention, what young people said they wanted was "someone to talk to, someone to understand what I was going through."

Different diagnosis, different prescription

The Australian ban is built on a specific theory of harm: that social media platforms, through addictive design and algorithmic amplification, are directly damaging adolescent mental health. According to the logic, remove the exposure and you remove the harm.

Haidt's The Anxious Generation makes a compelling case that the timing of the global teen mental health crisis – beginning around 2012 – coincides suspiciously with the mass adoption of smartphones and social media. He has been advocating for delaying smartphone access until age 14, social media until 16, and making schools phone-free.

But the Maldives report suggests that young people are less passive victims of algorithmic manipulation than active agents seeking support in the only places they can find it.

The report does not dismiss the risks of unvetted online support. It explicitly recommends that mental health campaigns include "clear and simple warnings about when to use AI chatbots for support and their limitations." But its core recommendations focus on building alternatives: community-based support, trained peer mentors, accessible screening tools, and services that reach beyond Malé to the rest of the country, home to nearly 60 percent of the Maldivian population.

The report's recommendations are extensive, but several stand out for young people specifically: schools need more counsellors and better ratios. Community-based mental health support, including peer groups, trained youth workers, trusted adults, needs to be built as a "first line" before specialist services. Screening and triage should happen in everyday settings so that young people with mild or moderate concerns get help early, rather than waiting until crisis point.

The report also advised leveraging the Maldives' high digital literacy rates by creating culturally adapted digital mental health tools that provide accurate information and appropriate triage. QR codes in schools, youth centres, even mosques could link to anonymous self-screening and confidential support.

"The path forward is clear and achievable," the report concludes. "Start by making care easier to find, safer to use, and closer to home."

If you or someone you know needs support, the National Mental Health helpline is available at 1677. The line is confidential.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.