Dr Hassan Hameed on his life's work: an English-Dhivehi dictionary eight years in the making

"Language can limit what can be thought and expressed."

Artwork: Dosain

16 Feb, 15:00

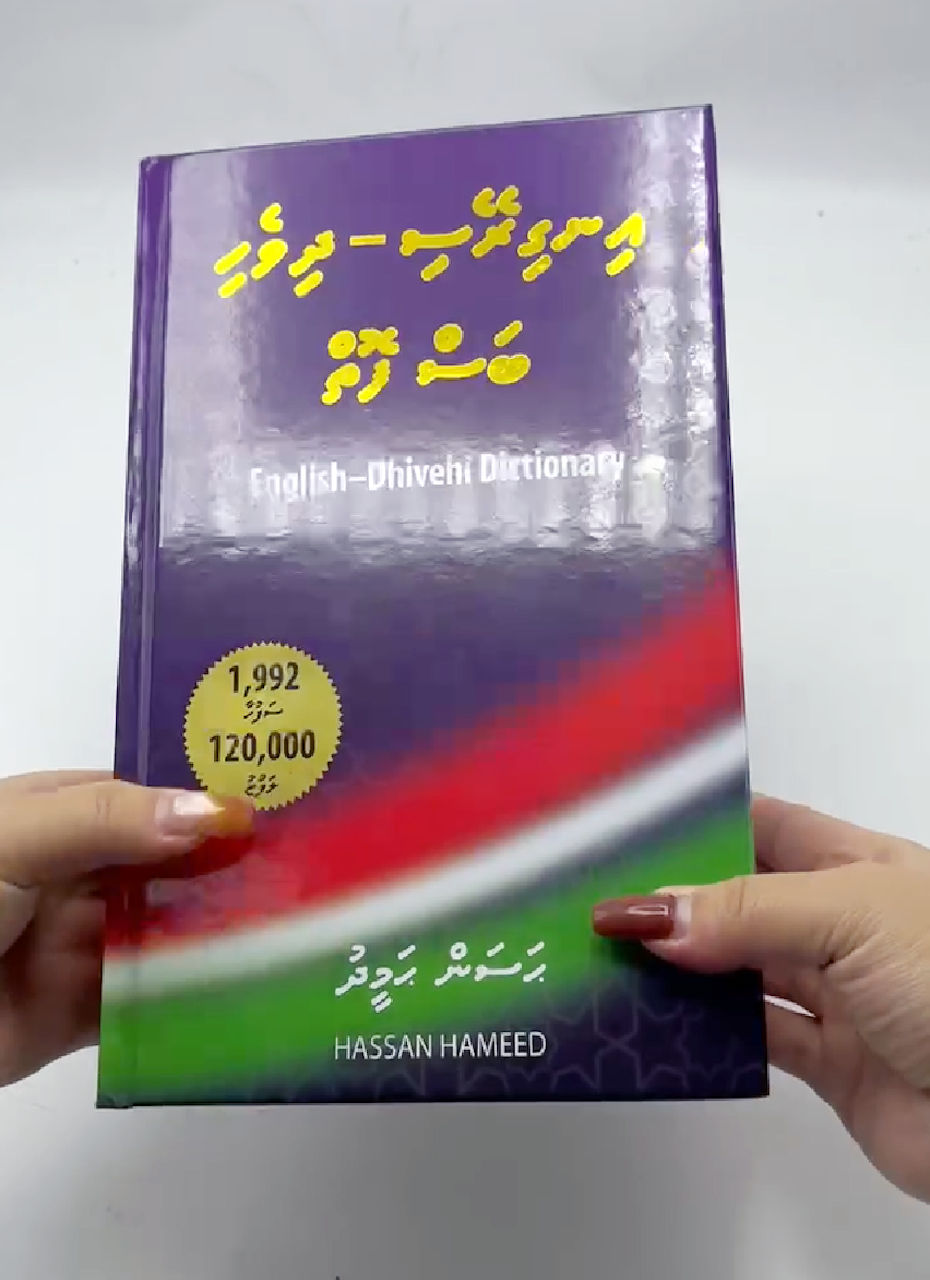

Dr Hassan Hameed has spent the better part of a decade compiling what will be one of the largest single-volume book ever published in Dhivehi: a 1,992-page English-Dhivehi dictionary containing 120,000 entries.

Hameed has served four decades in Maldivian education as a teacher, curriculum developer, and former vice chancellor of the Maldives National University. He is also a translator of classical Persian literature, a prolific typographer who designed many of the Thaana fonts used by Maldivian newspapers today, and the driving force behind the first single-volume Dhivehi dictionary in 2011.

For this project, he wrote every entry, typeset the book, designed the layout and cover, and built a custom font to keep the text readable at 9.5 points. We spoke to him about the art of lexicography, the limits of the Dhivehi language, and why he chose to work alone.

Is this dictionary a response to a crisis you see in how Dhivehi is being used or taught?

A project of this magnitude would have an extended provenance. I have long been involved in lexicography. Before 2000, there wasn’t a single-volume Dhivehi dictionary. The whole dictionary existed in loose booklets; each booklet lists words starting with a particular letter. Each booklet is called a Radheef (Arabic word meaning what follows, in the sense, after “Noonu ge Radheef,” Raa’s Radheef follows}.

In 1999, together with two friends, Dr [Abdul] Muhsin and Mr Adam Khalid (now both are at MNU), I met senior officials of the National Centre for Linguistic and Historical Research (NCLHR) and proposed that we collaborate to develop a single-volume Dhivehi dictionary. The dictionary was to be produced on a CD, with an option to print the entire work if required by the user.

At the time, Dr Muhsin was working at the Educational Development Centre and arranged for typists there to transcribe the multi-volume handwritten Dhivehi dictionary. The Bas (Language) Committee of NCLHR edited the typescripts and made the necessary amendments. Adam Khalid and I developed the software for the CD. Adam wrote the code for handling user input and searching the database; I wrote the code for printing the dictionary in book form from the same database. The CD was released in 2000 at the Writers’ Conference held in Malé. The CD was called Dhivehi Basfoiy 2000.

In 2011, NCLHR was dissolved by the government. A Centre for Dhivehi Language and History was established within MNU to carry out some aspects of the mandate of NCLHR. I deemed it essential to have a single-volume dictionary in printed form. Soon after, a single-volume Dhivehi dictionary was printed and made available to the public. It was over 1,200 pages long.

There were no authoritative English–Dhivehi dictionaries available in the Maldives. However, two dictionaries containing English–Dhivehi glosses are available. Consequently, it was recognised that an authoritative English–Dhivehi dictionary would be beneficial for students learning English. I compiled the meanings of all words beginning with the letter A, including usage notes for some entries and pronunciation for all entries, and published them in Dharuma as a supplement. Dharuma was a family magazine that was published for a decade in the early 21st century. Although the magazine typically sold approximately 3,000 copies per month, the issue containing the English–Dhivehi dictionary supplement sold 5,000 copies. This level of demand had been anticipated, and the entire print run was sold out rapidly.

Encouraged by this demand, I began to translate the remaining words. It was to take eight years, of which six years was full-time.

When multiple English dictionaries disagreed on definitions or usage, how did you decide which interpretation to follow?

Although every now and again new dictionaries are published, the definitions therein are remarkably consistent. Some newly published dictionaries contain definitions from the 1950s and 1960s. This is to be expected. In how many ways can you define an apple? Some meanings (and words) have fallen out of use; new meanings have been attached to some old words. In these cases, the most prevalent usage is considered.

What categories of words were hardest to translate – technical terms, abstract concepts, slang? Can you give examples?

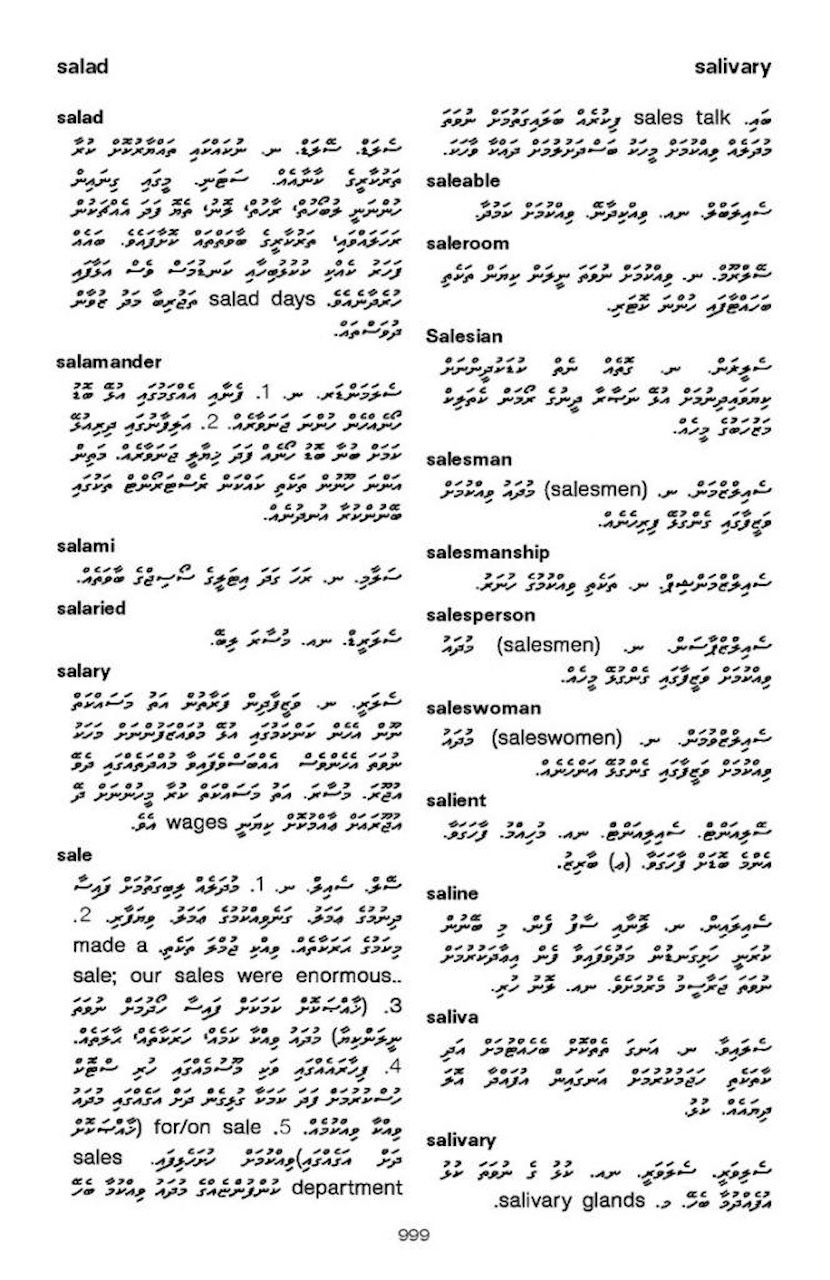

Technical terms and slang are not as difficult as abstract words. Words dealing with thinking are few in Dhivehi, which limits what can be expressed to explain the meaning of a word. For example, how would you differentiate the meanings of meditation, contemplation, reflection, musing and retrospection? The shades of meaning attached to these words are quite different. Language can limit what can be thought and expressed.

Oftentimes, there is a need to provide a gloss for common words (for example, normal, regular, et cetera). A dictionary is a reference book. The author has to be mindful that some readers may refer to the dictionary for a single Dhivehi word that expresses the same meaning as the English word (namely, a gloss). What is the Dhivehi word for regular for the sense that something is spaced out equally in time or distance? Finding such words may involve research that can extend into days or weeks.

How did you handle English words that have no Dhivehi equivalent? Did you coin new terms or find creative solutions?

A dictionary is different from a glossary which usually provides single word glosses for another word. It is useful to have Dhivehi words for some useful concepts. Word creation would require studying the etymology of the relevant word, researching the glosses for the word in other languages and studying related Dhivehi words. For example, what is the Dhivehi word for fact? Haqeeqath is not an equivalent Dhivehi word (for fact) and is too long. In coining new words, one has to be mindful of the Dhivehi linguistic features (morphology, semantics, syntax and phonetics) as well as the principle of parsimony for the word to be accepted. Authors often create words, though the authority for Dhivehi development is with the Academy. Suggested Dhivehi glosses are indicated in the book. I have studied the etymology of almost all such words in the English language.

A related complication in writing the dictionary is writing the pronunciation in Thaana. The phonemes present in Thaana are different from the phonemes of English. For example, the Thaana /r/ sound is different from the English /r/ sound. Some pronunciations cannot be written in Thaana. The last vowel of /family/ is longer than the short vowel ibifili and longer than eebeefili. In such cases what do you do? I have listened to the pronunciation of all the English words and written the pronunciation in Thaana in Received Pronunciation (RP) as best as I could. RP of common words are different from what we normally say in Dhivehi. Example is actually pronounced as /igzaampl/ in RP not as we normally hear in the Maldives.

Why design your own font rather than use existing Thaana fonts?

In order to produce the book as a single volume – to cram all within less than 2,000 pages – I have to use a font which is readable at small sizes. The printing house advised me that their machines cannot bind books with a higher page count. Because of the peculiarities of Thaana, text is unreadable in small sizes. The font I created is readable in 9.5 points and there are 37 lines per page. This text density was possible only with this font. By the way, most of the newspapers use fonts that I had designed over the years. You can read about new font here.

With 2,000 pages, the book could not have a glued ‘perfect binding.’ This is the reason why the book is produced in hard cover.

You've said dictionary work never truly ends. What do you see as the main gaps or weaknesses in this first edition?

There are many Dhivehi words that may constitute suitable glosses for English words. But these words are unknown to me so I have not included them. For example, I read today that there is a special Dhivehi word for incineration. Including this word would enrich the dictionary. Since printing, I have discovered more than a hundred such words in my research. I have also not seen the printed dictionary; I saw only photos. Scrutinizing the text layout can help improve the book. Additionally, extensive works of this nature are bound to have errors. I have come across errors in Oxford, Cambridge, Collins and Webster. Any reduction in the number of errors is an improvement.

The online version you're planning – will it be freely accessible? Was this entirely self-funded? What did it cost – financially and otherwise?

I have incurred a lot of expense in this task. Let me ask you a question: for how much will you translate a page of an English dictionary? How long will it take? What will be its quality?Now multiply that with six to eight years of work. Then you will get an idea of the costs involved. I enquired from a language teacher the fee she would charge to proof-read the book. She quoted MVR 250 per page. Now, multiply that by 1,992 pages. This is only for editing. Since the project is entirely self-financed, a free online version will not be available until the associated costs have been recouped.

Did you ever consider partnering with Dhivehi Bahuge Academy or other institutions, or was working alone deliberate?

There is some synergy in working within a group. A group can accomplish more than the sum of individual groups members. But this is possible only if the group members carry equal weight. Groups also tend to waste time. I did consider partnering with another person, but ultimately decided that my pace and time-on-task are not easily matched by others. More importantly, have you come across a novel written by two authors? Why are such novels so very rare? One has to know the plot and character development in Chapter 1 before s/he could write the later chapters.

You describe this as heavier than "two or three PhDs." What kept you going through the difficult stretches?

I have supervised several PhD students, both formally and informally, and have reviewed and edited many more doctoral theses. I am often puzzled that some of these works were accepted; a few decades ago, many studies for which students have been awarded this degree would have been rejected on grounds of academic rigour, quality of expression, and scholarly contribution. Higher education has now become an industry, and a customer-focused approach has subjugated academic rigour, scholarship, and learning for revenue.

An undertaking this long and demanding could only be carried forward by the deepest and noblest intentions: a desire to serve my country, and the quiet hope that, in the end, I could say my life truly mattered to the Maldives.

How do you think AI translation tools will affect Dhivehi, and does this dictionary have a role in that future?

At their current stage of development, AI tools are not truly creative, nor do they enhance a person’s critical thinking or intellect. This dictionary could help improve such tools only if they were trained on its words, along with their context and meaning – something that seems unlikely for many reasons. For now, my focus is on strengthening human thought by broadening perspectives and helping people move beyond the limits imposed by language.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.