Corruption hinders progress of health sector, says president

Solih acknowledged poor health services on all inhabited islands.

31 Jul 2019, 09:00

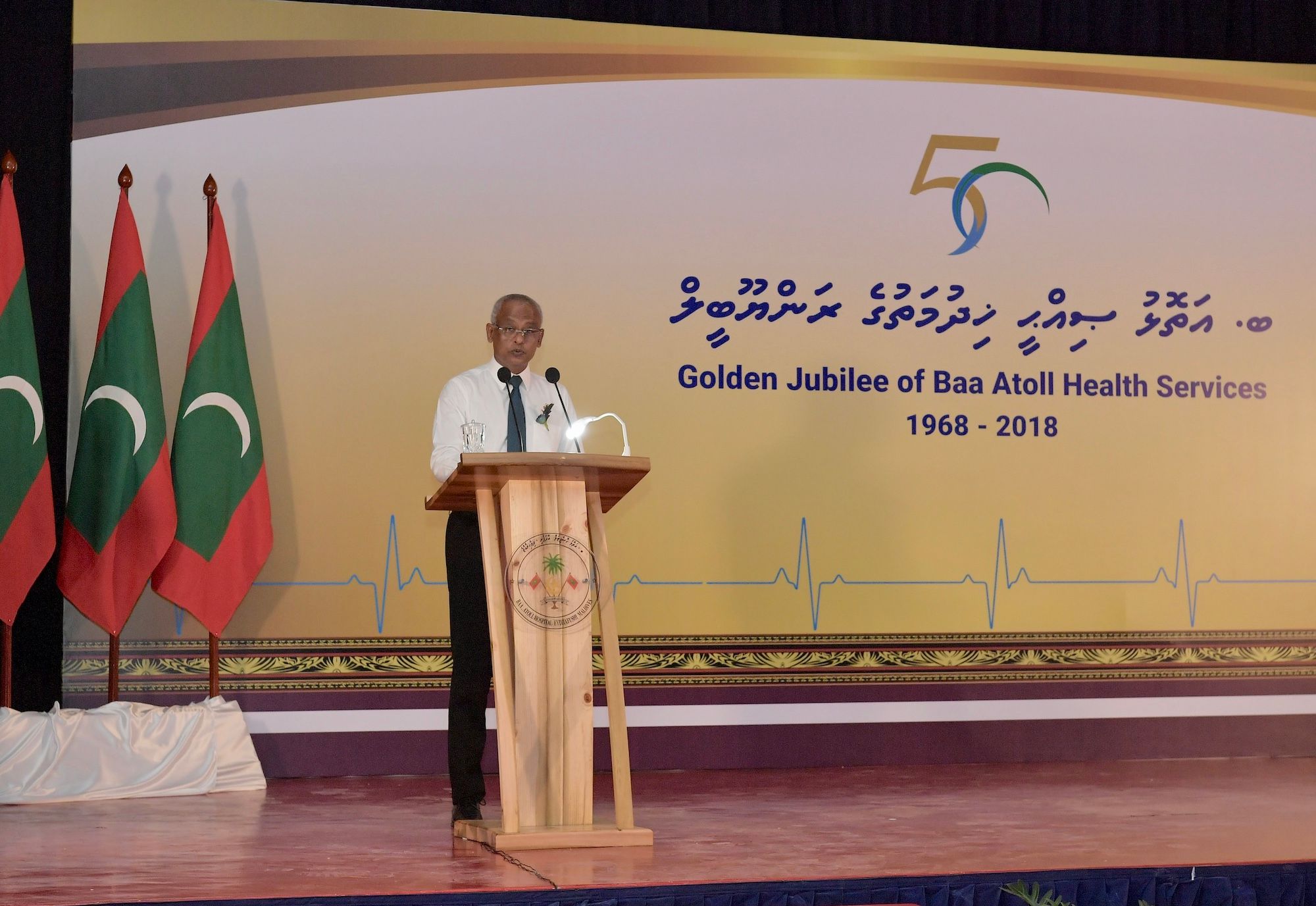

Corruption is the biggest problem facing the health sector, President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih declared at an event held on Tuesday night to mark the golden jubilee of health services on Eydhafushi island in Baa atoll.

“Schemes like Aasandha [health insurance] fail to achieve its true purpose and become a burden on the state budget because of corruption,” he said.

Last September, the World Health Organisation recommended an urgent review to make the scheme sustainable and more efficient. Introduced in 2012, Aasandha is a non-contributory scheme, without an annual individual financial limit, and can be used in some hospitals abroad.

It emerged in March this year that the anti-corruption watchdog was investigating suspected misappropriation of funds by former government officials.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.