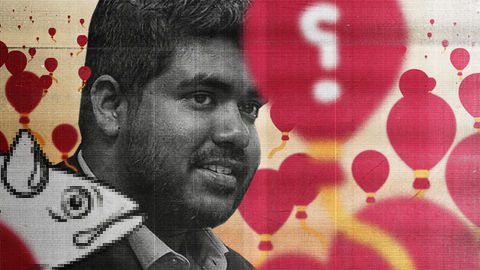

Episode 14: Suspended without pay – when decentralisation becomes punishment

Suspended without pay, Hoarafushi Council President Mohamed Waheed reflects on due process, accountability, and decentralised governance.

13 hours ago

Support independent journalism

Community policing belongs in the law. Don't gut it.

A former commissioner warns against dismantling trust-building reforms.

11 Dec, 5:43 PM

Banyans and saplings: 100 years old, replaced by inches tall

Ministry scrubbed tree height guidelines after replacing century-old banyans with inch-tall saplings.

10 Dec, 6:01 PM

Trousers for girls, beards for boys: school uniform policy reignites Maldives culture war

Girls must wear trousers from age nine under the new rules.

09 Dec, 6:18 PM

Why Maldivian courts have every right to try the FAM corruption case

Former PG Hussain Shameem dismantles the FIFA defence.

08 Dec, 4:56 PM

Death penalty for drug traffickers: What the new law says

Sweeping changes to sentencing, scheduling and rehabilitation.

07 Dec, 10:00 PM

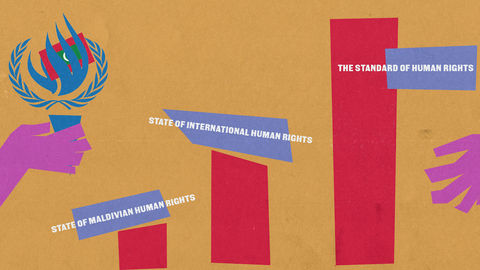

Dissecting decentralisation: how island councils are about to change

With more changes to the Decentralisation Act approved, we take a closer look at what is happening to local governance in the atolls.

04 Dec, 5:14 PM