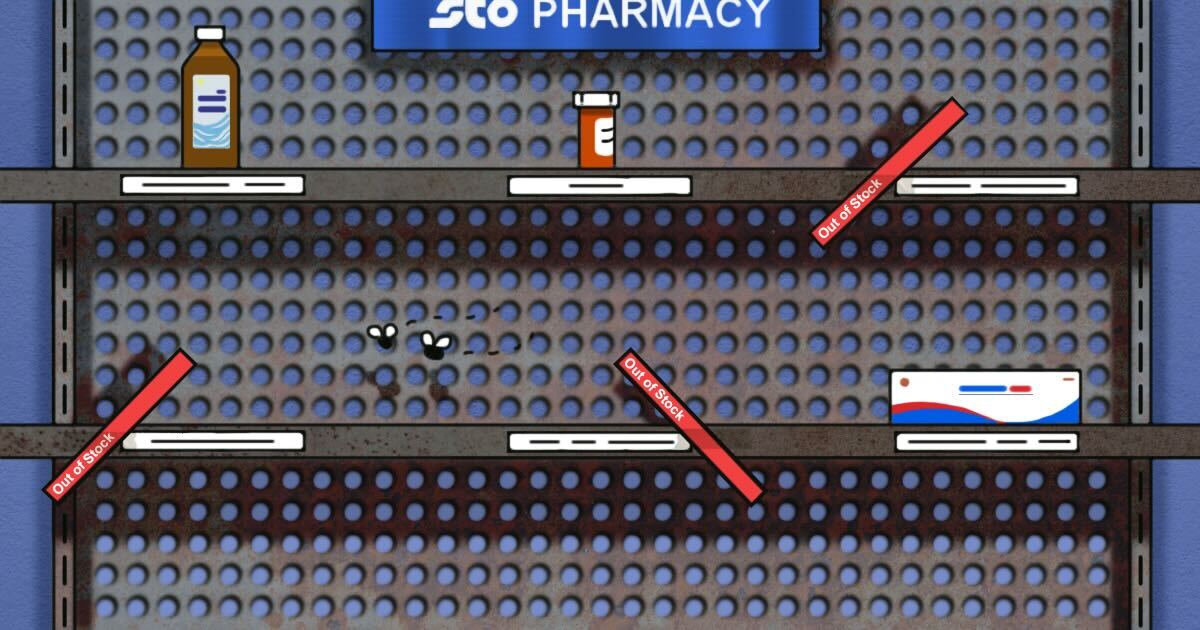

"No stock": Maldives grapples with severe medicine shortage

Maldivians seek life-saving medicines overseas as pharmacies run dry.

Artwork: Dosain

20 Feb 2025, 18:00

The prescription was simple: one Metoprolol pill daily to reduce the risk of another stroke. But for 70-year-old Adam Rasheed* and his family, filling this life-saving prescription became an impossible task. After searching every pharmacy in Malé, they faced a frightening reality: the medicine simply was not available anywhere in the capital.

As the family frantically reached out for help, they found hope through a friend in the healthcare industry, who managed to secure 40 out of the 90 prescribed pills. For the rest, the family looked to find someone returning from overseas.

“We are lucky enough to have known someone who managed to get it for us,” Rasheed's son said. "I can't imagine how hard it must be for someone who doesn't have that kind of connection.”

Rasheed’s predicament is symptomatic of a growing nationwide medicine shortage crisis. Stories of patients unable to access vital medications flooded social media in recent weeks. As patients with chronic conditions struggle to fill routine prescriptions, desperate families have been posting pleas on messaging groups and seeking contacts abroad.

The crisis stems from a complex web of issues: millions in delayed payments from the national health insurance scheme that have left importers without purchasing power, new price controls that have made it unprofitable for pharmacies to stock certain medicines, and strict regulatory requirements that made it difficult to import medicines for the Maldives' small market.

On Tuesday, the President’s Office acknowledged “financial difficulties and medicine shortages” and announced sweeping changes to address the problem. The eleven-point plan promised several immediate fixes: a dashboard showing medicine availability at state-run pharmacies, direct sourcing from manufacturers, and guaranteed access through new GP clinics in Malé. The announcement marked the first comprehensive response to the crisis. But it left unanswered questions about funding and the implementation timeline.

To uncover the root causes of the crisis, the Maldives Independent spoke to pharmaceutical businesses, government officials and a dozen doctors, most of whom wished to remain anonymous as they either work or consult at the main public hospital in Malé.

Worsening crisis

"This has been going on for around a year now. The situation has not improved but gotten worse. Now even some life-saving medicines are not easily available," a doctor said.

He took saline as an example of an essential item in short supply. The hospital was close to running out of IV bags used to replace lost fluids, he said.

"And this is the situation in Malé. It is only worse outside the capital."

Doctors have been calling colleagues at other hospitals to see whether a particular drug was available. Some have resorted to social media to seek help with bringing medicine from abroad.

The impact is particularly severe in psychiatric care.

A family member of a schizophrenic patient who suffered a breakdown after running out of medication told the Maldives Independent about admission at the Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital’s psychiatry ward after an ER visit.

The small IGMH ward was at full capacity with patients tied to their beds. What she witnessed there highlighted the devastating toll on mental health. "There were about five people with psychiatric issues admitted because of self-harm or trying to harm others,” she recounted.

“This is all because of the medicine shortage."

Conflicting explanations

One of the main suppliers of pharmaceutical products is the State Trading Organisation. Amid mounting public concern earlier this month, the state-owned company denied any shortage of essential medicines.

But Shimad Ibrahim, STO’s managing director, blamed doctors for allegedly writing prescriptions with specific brand names instead of generic medicines.

"Doctors prescribe medicine based on the symptoms of a patient or based on a diagnosis. But if they write a brand name, that brand might not be available at the STO pharmacy," he told Mihaaru.

Shimad went further, accusing doctors of prescribing medication that was not on the "approved drugs list." Registering a new drug on the list is a lengthy process, he said.

Generic names refer to a drug's chemical composition. Brand names are versions marketed by different manufacturers. For instance, the antihistamine Fexofenadine is sold as Allegra, Ultigra, and Fexofen.

On February 10, the Maldives Medical Association disputed Shimad’s claims. Aside from exceptional cases such as allergies to some medicines, doctors write generic forms “in alignment with Aasandha policy,” the association said.

But some doctors slammed the statement as "toothless" and "cowardly".

"STO is lying. Why can't MMA clearly say that STO is lying?" a doctor from IGMH told the Maldives Independent.

Medical prescriptions are issued through Vinavi – a centralised database administered by Aasandha, the state-run health insurance scheme – where doctors must select medicines from a pre-approved list that matches the patient's diagnosis.

"Doctors can't just randomly prescribe medicine through the system,” a super-specialist explained. “There is a drop-down box listing medicines that can be prescribed and doctors have to choose from this database of medicine. Then you also have to make sure that the medication is related to the symptoms or diagnosis.”

But doctors do specify brands in situations such as patients who were “more comfortable with a particular brand because they have used it for a long time,” she added.

The Medical Association also defended “the right to prescribe a preferred brand in situations where prescribing the brand is more beneficial to the patient”.

All the doctors who spoke to Maldives Independent denounced Shimad's claims – which had set off a blame game among doctors, suppliers and regulators – as either “lies” or “half-truths.”

Cash crunch

A key factor that exacerbated the medicine shortage is the government’s ongoing cash flow constraints, a wider problem with repercussions felt throughout the economy.

Last year, payment delays briefly ground some industries to a halt, including construction and fishing, where local businesses rely on government projects or sales to a state-owned company, respectively.

The arrears created a purchasing power crisis within the healthcare and pharmaceutical industries. All major companies in the sector rely on payments through Aasandha.

ADK, one of the largest private hospitals, was owed MVR 250 million (US$ 16 million) from Aasandha.

ADK Chairman Ahmed Nashid told a parliamentary group that the hospital had been seeking payments since October 2023. The revenue shortfall has affected ADK's ability to buy and import life-saving drugs, he told lawmakers.

Smaller pharmacies and importers were facing the same challenges with millions held up due to delays in Aasandha payments.

“There’s no money. Not in the entire country. We can’t do it if there isn’t any. We’re issuing medicine for credit, expecting Aasandha to pay. What can we do if Aasandha doesn’t pay? They already owe millions,” an exasperated private importer and wholesaler told the Maldives Independent.

Price control dilemma

The medicine shortage followed new price control measures introduced by Aasandha in a bid to save MVR 220 million from the increasingly unsustainable scheme.

Rolled out in phases during November, the prices of 250 "widely used" drugs were capped with prohibitions on retail prices above the new rates.

Before the price caps took effect, Aasandha assured the public that the accessibility of medicines would be unaffected. Medicine will be available without additional cost through STO and Aasandha-registered pharmacies, the company said.

But small pharmacy owners found that wholesale prices were higher than the Aasandha caps.

A blood pressure medication called Telmed H illustrated the problem. "Aasandha is asking pharmacies to sell at a loss. The wholesale price is higher than the Aasandha price," a small pharmacy owner said. The pill costs MVR 5 from wholesalers but was capped at MVR 3.30. "Initially, we were told we can ask the consumer to pay the difference but then they reversed it and said we have to sell it at the capped price," he said.

The unaffordability of drugs for smaller retailers disrupted the pharmaceutical supply chain as wholesalers stopped importing until they could sell off existing stocks.

Small businesses faced other issues unrelated to Aasandha policy changes.

"Even STO, they can't [import]. We have been told so many times about different medicine stocks that STO does not have enough to sell to retailers,” a pharmacy owner in Addu City said.

“They barely have enough stock for use in their retail outlets.”

One of the proposed solutions is a UNDP global health procurement service, which allows 33 small nations to pool their resources and bulk purchase drugs. It promises high-quality medicine at lower cost and STO signed on in June 2023. But only 10 drugs are being imported so far. It will take considerable time before the system can cover all essential medicines, according to experts.

Regulatory hurdles

In December, the Maldives Food and Drug Authority introduced new medicine registration rules that assured an easier path for import approvals. But the changes appear to have reinforced existing barriers.

MFDA's drug approval process requires importers to submit a Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) dossier before adding products to an approved drugs list. This extensive documentation, often thousands of pages long, covers manufacturing processes, quality tests, clinical studies, and packaging standards.

But manufacturers only release GMP dossiers to importers who commit to minimum order quantities. Importers must also submit independent lab results verifying the medicine's composition.

This created a catch-22 situation.

“Let’s say there is a specific medication that is needed. To get on the approved list for import, we need the files. For the files, we need to buy from the manufacturer, but they will only sell to us if we buy, let’s say 100,000 items. But we cannot sell 100,000 in Maldives. There is no market for that,” an importer explained.

GMP documentation must be up-to-date. Any product changes, including rebranding, requires new documentation to renew permits.

“You need this for any change. Even dosages. For example, medicine X is already on the approved list for 50mg. If there is a new version that has 75mg, it needs to go through the whole approval process,” the importer said. “Then maybe the doctor needs to prescribe the 75mg one, they will have no choice but to tell patients to take one and a half pills of 50mg, to meet that 75mg required dose.”

When manufacturers switch production partners, importers must submit entirely new GMP documentation. The high minimum orders force importers to buy more stock than they can sell, driving up local prices.

“If the MOQ [minimum order requirement] is 50,000 bottles of a medication [for instance], the importer has to commit to buying that. But in the Maldives, before expiry, we can only sell 400 bottles,” the importer said. “So who is going to cover the loss? What is the importer going to do? The importer has no choice but to cover the loss by marking up the price of the medicine.”

MFDA defends system

MFDA acknowledged the challenges of the GMP system for a small, import-dependent market.

This was why the new rules introduced an easier option known as the “reliance” path, according to Aishath Jaleel, MFDA’s director of enforcement for pharmaceuticals.

The easier path expedites the process for medicine pre-approved by a “stringent regulatory authority” consisting of 45 national agencies that meet WHO criteria, primarily based in Europe, North America and Oceania. The closest to South Asia are the Singaporean, Malaysian and Indonesian authorities.

"For the reliance path, importers need to apply and include documentation to show that they are going to import the same medication made by the same manufacturer in the same factory outlet as the medication that has been approved by the relying regulatory authority," Aishath said.

She defended the stringent requirements and insisted that these standards were necessary: "Our current system is as lenient as can be. If we relax the rules any further we will be compromising on the quality and efficacy of drugs. That is our top priority, to ensure safety, quality and efficacy. If those standards are not met we are talking about low quality and even fake drugs."

Her concerns were not theoretical. There have been cases where even approved drugs did not meet quality checks.

"We do post-market surveillance after the product is imported," she explained. "This is qualitative and quantitative studies and we have seen instances where the product is in the same packaging and branding, but there are deviations from the quality parameters set by the manufacturer of the product. So we have to take action."

* Name changed to protect privacy.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.