A lingering longing for self-rule

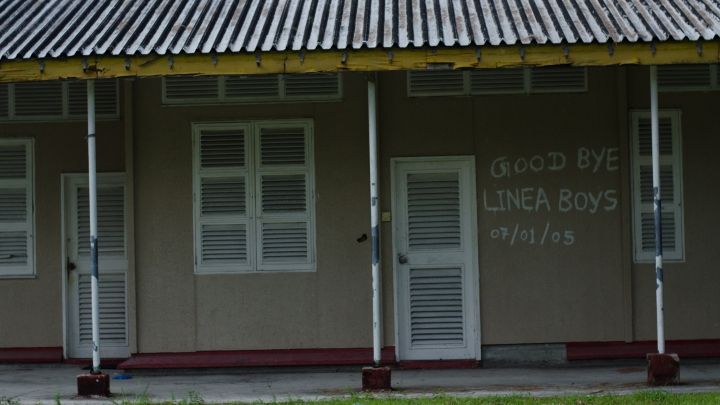

In Addu, on the eve of the Golden Jubilee of independence, stories of the short-lived United Suvadive Republic are told and retold and the longing for self rule lingers on.

26 Jul 2015, 09:00

On the night of December 31, 1958, in southern Addu Atoll’s Feydhoo Island, a protest was going on against the central Malé government. Hundreds were protesting against the government’s refusal to pay salaries to those employed by the British. The Maldives was a British protectorate at the time.

Ahmed Jaleel, who was just 15, told me how events transpired.

“You see, the British paid our salaries in Pounds to the Maldivian government. In return, the government paid us in Rufiyaa. But in October 1958, they abruptly stopped doing so. After nearly two months without salaries we protested,” he said.

Jaleel, a tall, slender man with a full white head and beard, is now 72. At 15, he had a job on the military base on Gan Island.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.