Malé and its discontents

“In many ways, Malé is a thoroughly modern city, living out all of modernity’s problems (with a few of its pleasures) in a microcosm, fighting to keep its head above water on five square kilometres of submerging land. What Malé is today is shaped by the daily struggles, victories and defeats of its hundred and fifty thousand residents from everywhere in the Maldives,” writes Dr Azra Naseem.

17 Dec 2015, 09:00

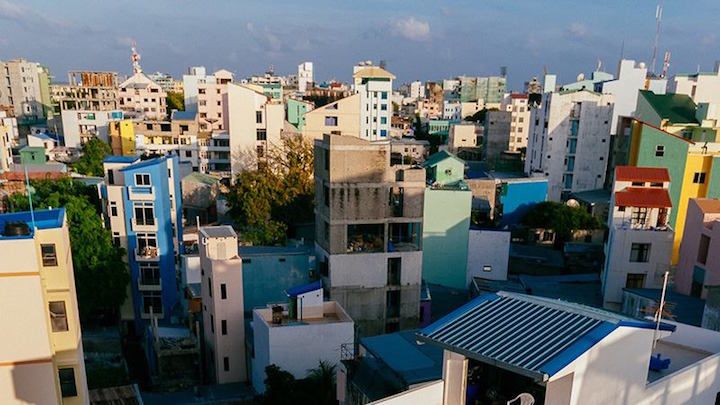

Malé, the capital of Maldives. Less than six square kilometres of land on which 150,000 people live, crammed into small apartments in thousands of high-rises determinedly cemented into low-lying land just one metre above sea level. Over at least 25,000 motorbikes zoom about on its narrow lanes, weaving in and out of lines of hundreds of unnecessary cars, status symbols choking the earth. People spill over onto the busy roads, forced to face oncoming traffic in the absence of a walk-able pavement. Children cling desperately to the hands of their parents, are belted onto motorbikes, or are being driven in another unnecessary car. A leisurely stroll to school without fear of traffic on speed is not an experience the young in Malé have ever known. Malé folk talk loudly, move largely in groups, and almost everyone is connected to the world with a Smart Phone. People look the same but are somehow different, dressing to belong to one or other clan of the times. Men wear beards, some as Salafis, some as hipsters. Many women could be from the streets of New York while others could have stepped out from a Saudi home. People argue, laugh, have coffee, cry. They eat Supari, spit loudly, read poetry, eat lovely fish curries and cupcakes, protest, and keep a rolling conversation going on around the streets, and on social media. Malé is rarely quiet, always busy and looks like it may topple over any minute. The ‘sunken island’, some have called it.

Most residents of Malé today come from everywhere in the archipelago. One third are Bangladeshi workers. Their presence in Malé, Maldives’ (mal)treatment of them, and their impact on the life of Maldivian economy and culture is a story in itself, for later. Lives of Maldivians themselves in Malé are hard, its trajectory and flow controlled largely by exorbitant rents beyond reach of ordinary Dhivehin. Years of development with a narrowness of focus that excluded islands far from, or regarded as unimportant by Malé, have forced people to move to the capital. Many formerly thriving islands are now desolate, their houses—both poor and well-off—abandoned by families forced to pack their bags and head to Malé. From the island of Vaikaradhoo, 13 families emigrated to Malé last year alone. Local newspaper Haveeru tells a story of abandoned lives of people who left for Malé, and people who have been abandoned by those who left for Malé.

The high demand for property in the capital has created the sharpest of divisions in the socio-economic makeup of Maldives today: the divide between people with land in Malé and those without. Things are about to get worse with the new 15% property tax all—even first-time— buyers must pay. On top of the new tax, all buyers have to also shell out for a 6% GST, which brings taxes to 21% of the value of the property. An added burden, which must also fall on the buyer, is the 20% deposit required to secure a home loan that would put the property within reach. Haveeru calculated that any prospective property buyer in and around what the government is calling the Greater Malé Area, must have 41% (MVR 820,000) of the average property price set at around MVR2 million. In a country where the average salary is around MVR5,000, buying property is a dream well beyond reach for almost everyone.

Thousands of land-owning Malé people, all of whom inherited their houses or plots before land became gold, have moved to neighbouring countries: often Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, and Singapore; or to Australia, the UK, the US and, sometimes, the Middle East. Their houses in Malé are in turn left to be rented by the thousands flowing in to Malé. The rental income pays for not just their children’s education but also covers their own rental homes in the countries they have relocated to. Such moves are not always motivated by desire; most often it arises from a necessity. Those who leave have better access to education, health, sanitation, and human freedoms than all other Maldivians. People in Malé have less. People in the islands lesser.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.