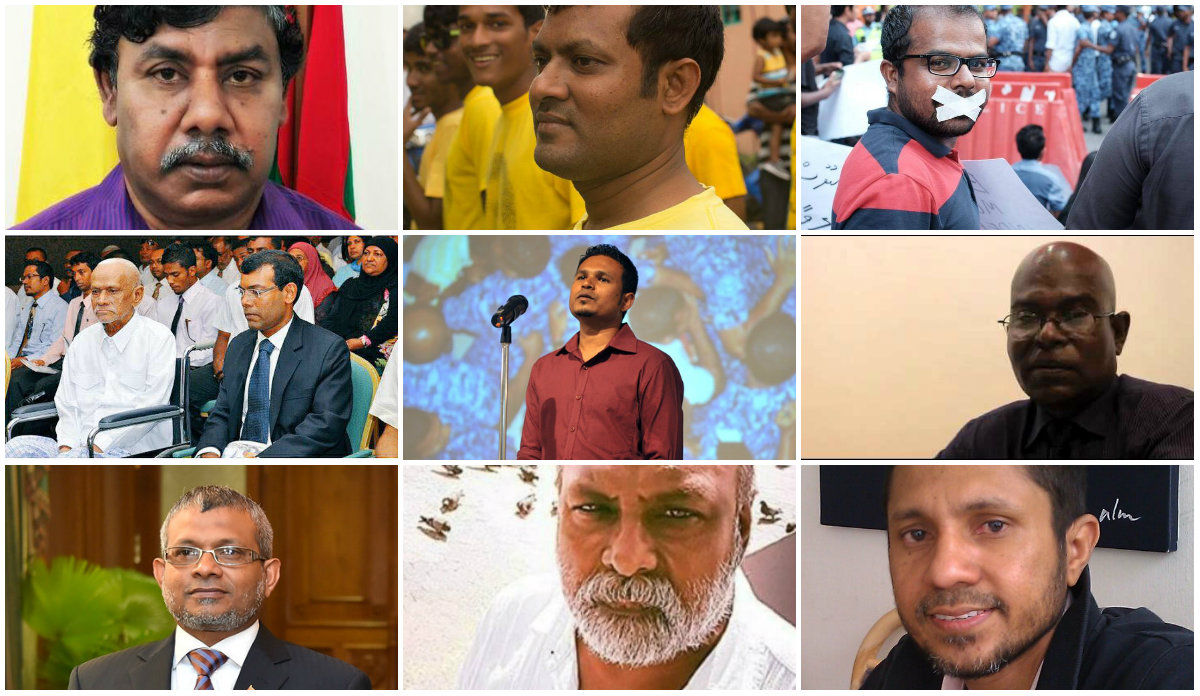

Locked Up: 13 writers whose words were held against them

On World Press Freedom Day, The Maldives Independent profiles 13 men – dissidents, writers and journalists – who suffered prison, solitary confinement, prosecution, and torture for their written words.

03 May 2016, 09:00

On World Press Freedom Day, The Maldives Independent profiles 13 men – dissidents, writers and journalists – who suffered prison, solitary confinement, prosecution, and torture for their words, written on newspapers, magazines, leaflets, mailing lists, websites and their own personal diaries.

Abdul Majeed Shameem, reform activist

Abdul Majeed Shameem, known as Majeed Sir, was arrested and sentenced in 1990 for leafletting. He is now a member of the opposition Maldivian Democratic Party.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.