Development or environment: A dilemma for Maldivians

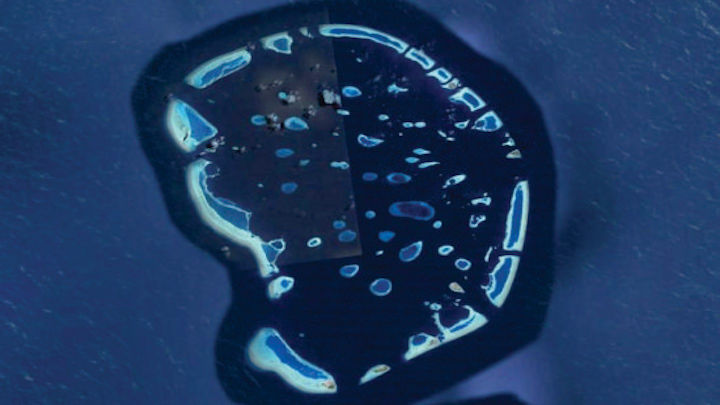

Aside from the irreversible damage to fragile reefs from reclamation and dredging, the Maldives stands to lose the unique Islandness (ޖަޒީރާވަންތަކަން) of an ancient ocean civilisation, writes environmental scientist Ibrahim Mohamed.

12 Mar 2017, 09:00

“Pretending that we have to choose between the economy and the environment is as harmful as it is wrong” – Justin Trudeau, Canadian Prime Minister.

The news of the Saudi royal family’s desire to invest billions of dollars in a Special Economic Zone development project echoed loudly on local media recently. Many locals including several parliament members have raised concerns over losing sovereign rights of Faafu Atoll from this project. The Special Economic Zones Act allows foreign ownership of land for a period of 99 years and provisions on residency to foreign nationals within the SEZ.

Legal interpretations of the Act are essential to understand the implications of such a project to sovereignty of islands acquired under the SEZ Act. Below are a few clauses quoted from the Act for readers to ponder;

Clause 80: on SEZ residency

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.