Crowded out by Concrete

The Maldivian population is 338,434, almost 40 percent of which lives in a congested capital that measures 2.2 square miles.

24 Mar 2018, 09:00

The Maldives is advertised globally as an idyllic holiday and honeymoon destination. But its people seldom access these picture-postcard perfect resorts unless they work on one or own it. Whatever natural beauty locals have left in this ‘paradise on earth’ faces destruction in the name of development.

Whether it is closing off a surfing spot to make way for a multimillion dollar bridge, razing mangroves or attempting to sell an entire atoll, President Abdulla Yameen’s government has come under fire for crowding people out with concrete.

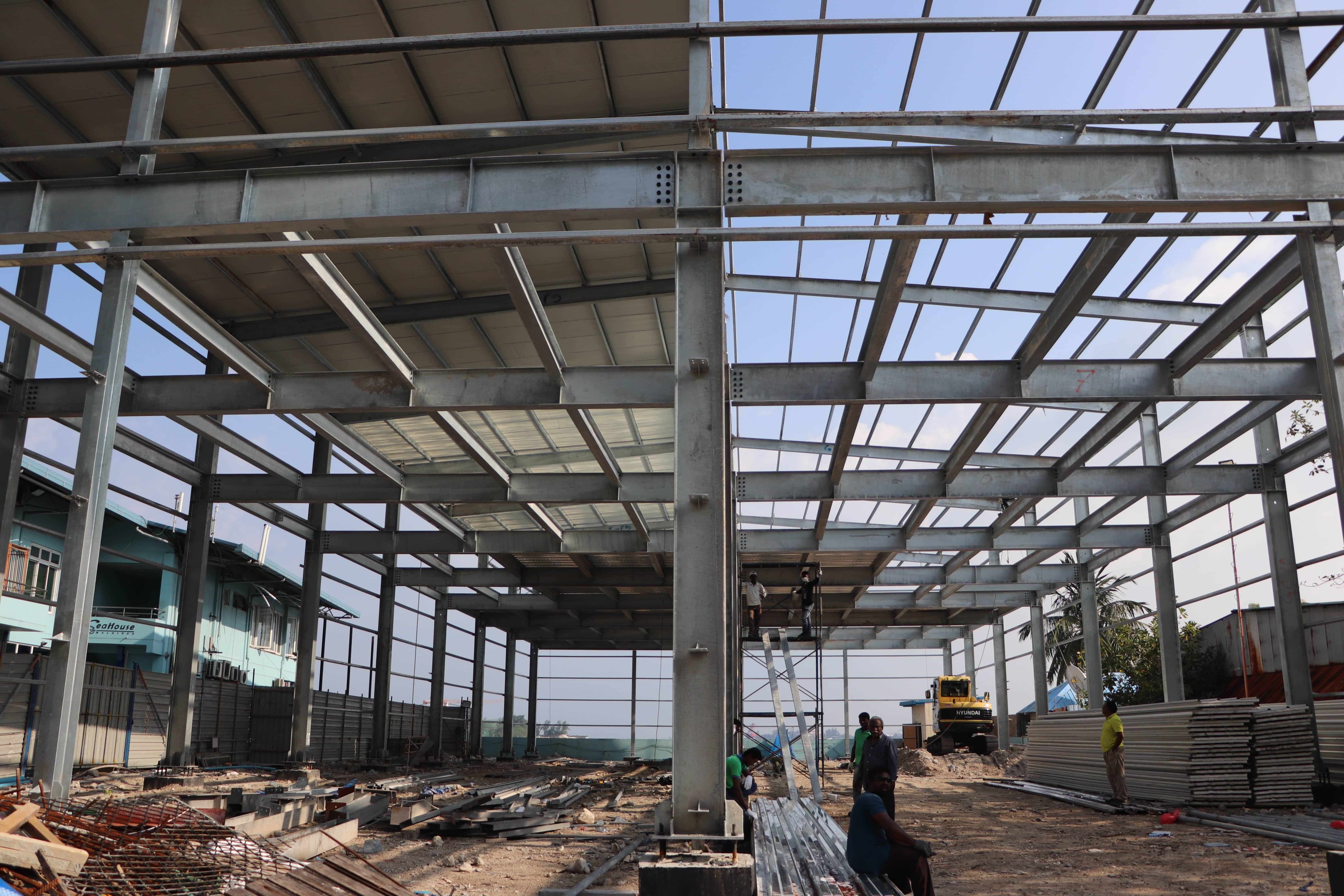

The already-congested, almost oppressive, capital is an obstacle course of heavy machinery, dust and scaffolding. Neighbouring Hulhumalé is the scene of an ambitious resettlement project and all the construction, noise and pollution that such a proposal entails.

Lawyer and surfer Ahmed Amir* has spent most of the past four years at sea, taking a 20-minute ferry ride between the capital and Hulhumalé. He used to hang out at Raalhugandu in Malé.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.