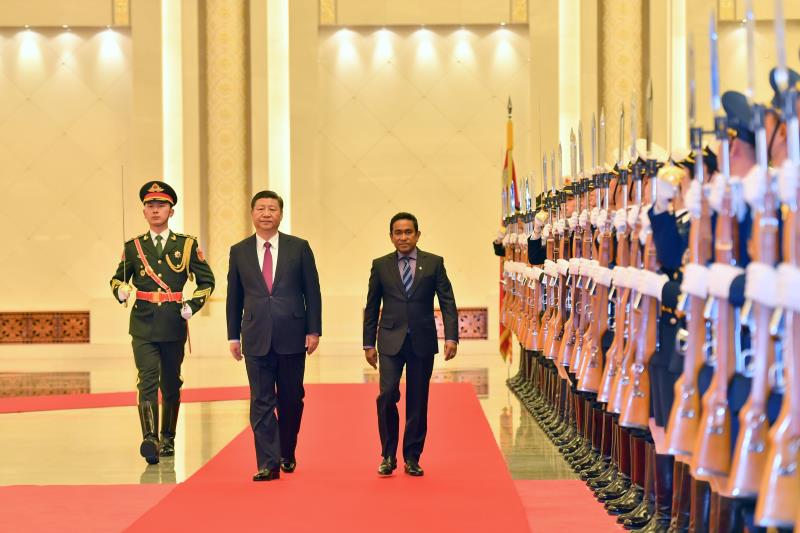

China, debt and the Maldives

The IMF and World Bank say major building projects have the capacity to transform the Maldivian economy, but are concerned about the high debt being fuelled by the infrastructure scale-up.

27 Mar 2018, 09:00

Chinese lending is putting the Maldives at risk of debt distress, a study from the Center for Global Development said earlier this month. But what is debt distress and why should Maldivians care about it?

“With debt distress there is a liquidity issue and a solvency issue,” says one of the study’s authors John Hurley. “Liquidity is: ‘I can’t pay you today but I think I can pay you tomorrow.’ Solvency is much more serious. ‘There’s no way I can pay you without having to cut back to the bone.’ Debt distress means you can’t pay the debt normally.”

The study says China is heavily involved in three major projects: an upgrade of the international airport costing around US$830 million, the development of a new population centre and bridge near the airport costing around US$400 million, and the relocation of the major port.

In addition, the government has given a sovereign guarantee for a US$370 million Chinese loan. The terms for all of this financing are unclear as neither state is famed for its transparency.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.