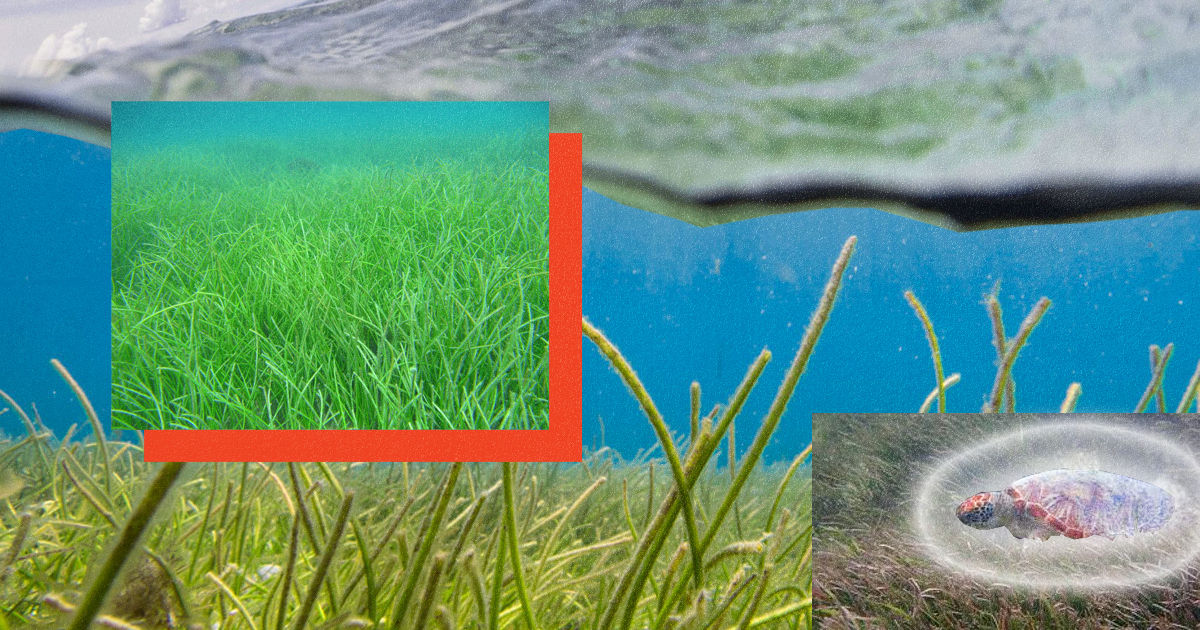

‘Ugly’ seagrass meadows vital for atoll survival

Seagrass meadows grow islands, protect reefs and store carbon, but are often removed for aesthetic reasons.

Artwork: Dosain

Sand production

Reef protection

Role in biodiversity

Blue carbon storage

Steps forward

Establishment of a policy expert group dedicated to analysing the effectiveness of seagrass related policies and provide actionable recommendations. This should encompass the integration of seagrass preservation into marine construction plans, ensuring that such projects avoid causing harm to these ecosystems or disrupting critical sediment transport pathways.

Active restoration efforts to reduce fragmentation, reconnect habitats, and recover lost or damaged seagrass meadows.

Assisted migration to increase genetic diversity, especially in genes that are more resistant to higher temperatures

Community awareness programs to increase awareness on the importance of seagrass ecosystems

Encourage and prioritise research into seagrass ecosystems, with a particular focus on addressing existing knowledge gaps, exploring underrepresented areas, and formulating effective strategies to safeguard their ecological and economic significance.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.