Maldives navigates shifting monsoons and weather extremes

Record rainfall in Malé on January 3 was an extreme weather event.

Artwork: Dosain

11 Feb 2025, 11:00

The concrete barrier bore the marks of desperation, detritus of a hammered-out opening for rising floodwaters. It flowed out to Malé’s western artificial beach, offering an outlet for the capital’s battered thoroughfare.

The makeshift drainage channel was dug out on January 3, when the streets were inundated for hours in knee-deep water, as city officials and emergency workers scrambled to respond to nearly 800 flood reports from homes and businesses.

Malé – a concrete-packed island barely two square kilometres in size – is prone to flooding even with moderate rain. The city has a well-documented and meme-filled history of flooded streets and sewage leaks. What was unprecedented was the ferocity of the deluge – a record 110mm of rain within a three-hour window.

“It was an extreme weather event,” Ahmed Shabin, the senior climatologist at the Maldives Meteorological Service, explained. “Even if we can’t show that from long-term weather data, we can now observe these changes that have been forecasted in climate predictions.”

Meteorologists are beginning to see what he described as the “high intensity, high frequency” events that are predicted to become more common as temperatures climb. “The prediction of climate scientists is exactly what we are experiencing now,” he said.

In April 2024, “feels like” temperature in Malé reached a record 46 degrees Celsius. Global temperatures exceeded 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels for the first time last year, blowing past the target of the 2015 climate accords, disrupting weather patterns and spelling an uncertain future for the Maldives.

Rainfall patterns will change with the rising heat, Shabin said. But the Maldives could be spared the more devastating impacts seen elsewhere. A cyclone is unlikely due to a safe location atop the equator. “It’s more likely that we face the impacts of systems that form near the region,” he suggested.

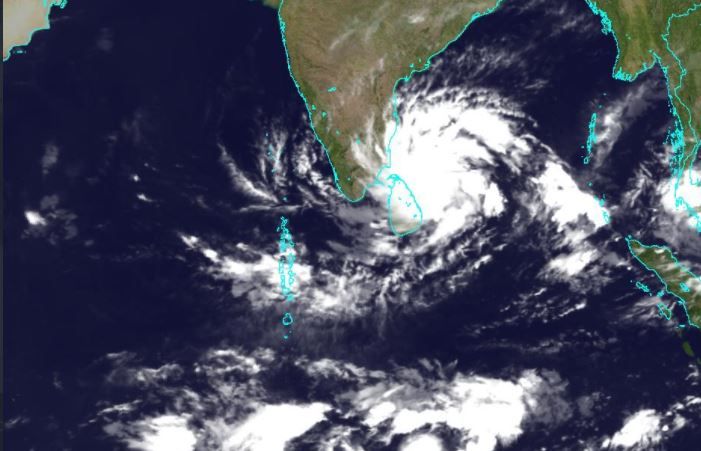

Cyclones in the region do not usually enter the Comorin Sea. They form west of Sri Lanka, move towards the Bay of Bengal and get deflected towards Odisha or Bangladesh. Those forming in the Arabian Sea move towards Oman or Pakistan.

“But now, in the past two years, we are seeing more cyclonic systems forming in the south of Sri Lanka and going towards the Arabian Sea, where they become fully-fledged cyclones, which means these systems are forming in very close proximity to the Maldives. So if it deflects, even if there is a slight change in angle, there is a possibility of it going over Maldives [in the northern region],” Shabin explained.

“It hasn’t happened yet, but because this keeps happening more and more, by chance that is a possibility.”

The new abnormal

The January 3 record downpour reflected a growing trend reported across the country. Days’ worth of rain now falls in hours.

“Observations and lived experiences are also climate records,” Shabin said.

In Malé, household damage worth MVR 2.2 million (US$142,670) was the worst in the capital’s history, according to the National Disaster Management Authority, which provided sandbags and arranged temporary shelter for 226 people from 36 households. It was the largest operation ever conducted in response to flooding.

Eight other islands reported damages. Faafu Nilandhoo was the worst hit with 80 percent of the island flooded. Closer to Malé, Kaafu Himmafushi reported damage to 60 percent of households. Further north, Raa Inguraidhoo and Shaviyani Maroshi faced damage from swell surges.

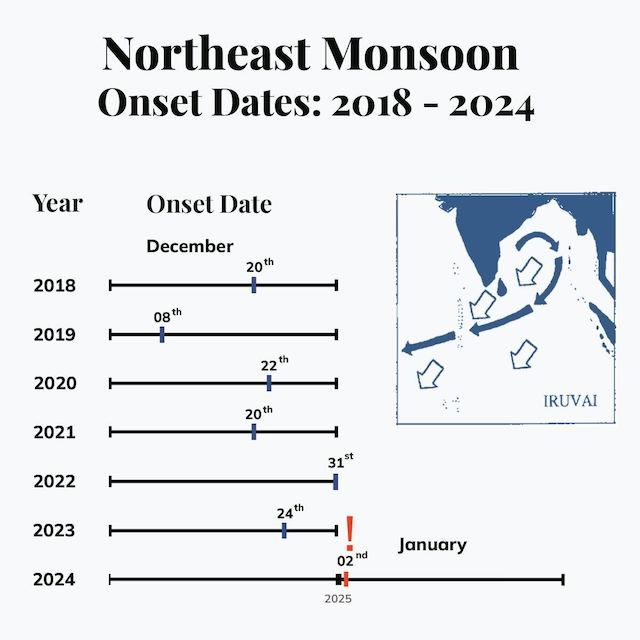

When the rain finally relented, the Met office officially confirmed the onset of the northeast monsoon on January 2. Called iruvai in Dhivehi, the dry season traditionally begins in mid-December. But this year’s onset was the latest recorded since the Met office started collecting data seven years ago.

The wet southwest monsoon known as hulhagu normally extends from mid-May to November. December and April are transitional months.

Abdul Azeez, a farmer from Laamu Fonadhoo, was growing about 2,000 watermelon trees in 150 beds when the skies opened. Submerged under rainwater, most of his crop did not survive.

"The new year rain affected everyone here. I expect the price of watermelon will be high this Ramadan,” he told the Maldives Independent.

Laamu atoll is a major supplier of watermelons along with the better-known island of Thoddoo, he said. Watermelon juice is the most popular iftar drink during the fasting month.

Azeez fared far better than most in the flooding. His losses on the open farms could be offset with produce from six greenhouses built under a small grants project. Employing vertical farming techniques, he is growing about 260 watermelon trees in addition to cucumber, lettuce and melon.

"I think this is the way to sustainably do farming in Maldives now. We are getting heavy rainfall throughout the year now, not just in hulhangu. So, if you want to be sustainable, you have to do smart farming," he said.

Ancient wisdom

Abdul Maajid Hussain, a fisherman from Laamu Hithadhoo, recalled how the monsoons have changed since he began fishing more than 38 years ago. “The strong winds and heavy rain we are used to seeing in hulhagu can be seen in iruvai too," he said.

But fishing has been excellent of late, according to Maajid. His tuna boat hauled in a large catch near a buoy east of Meemu atoll last week, he said.

As seafarers and fishermen, the rhythms of ancient Maldivian life were closely intertwined with the monsoons. Iruvai was associated with bountiful fishing, particularly in the northern atolls, ushering in trade winds ideal for sailing to the subcontinent. Hulhangu brings rain that forces fishermen to stay closer to shore. The onset of the southwest monsoon was traditionally the signal to start collecting and building up rainwater reserves for the dry season.

This ancestral knowledge was embodied in the nakaiy calendar, a codified system of two-week intervals that guided Maldivians through monsoon cycles. Each fortnight has distinct characteristics, often marked by the abundance of a species of fish. Mula, the first nakaiy of iruvai, is good for tuna but bad for bonito. Livebait is plentiful in the northern atolls.

Juxtaposed on the Gregorian calendar, the period falls between December 10 and December 22. But nakaiy was largely based on observation of capricious tropical weather. It was never perfectly predictable, fixed and locked to the modern calendar as now. The peg offers “no leeway for adjusting it based on weather observations, which is why we don't see so much of an alignment,” said Shabin, the climatologist.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that nakaiy predictions – derived from Sri Lanka and southern India – were more reliable for the northern atolls. Rainfall patterns are different for the north, central and southern regions, Shabin stressed.

Tropical uncertainty

Unlike wind or temperature, rainfall is intrinsically harder to forecast and the Maldives lacks fine-tuned data that goes back decades. This prevents drawing statistically significant conclusions, Shabin explained. Current Met office data is limited to five stations across the Maldives, an archipelago that stretches 90,000 square kilometres over the Indian Ocean, an area larger than Ireland, Portugal or the UAE.

But there are some recognisable patterns. Southern islands get the most rain but lower average wind. Northern atolls experience stronger winds. Central and southern regions experience two rainfalls peaks in May and October or November. In the north, southwest monsoon rains fall in May and last longer, peaking around August.

According to Shabin, several factors might have delayed the onset of the northeast monsoon, including the El Nino warming pattern that spiked sea surface temperatures last year. Towards the end of 2024, consecutive circulations formed near the Maldives, possibly thwarting iruvai winds, which must be sustained for two days for the onset to be declared.

But a late iruvai does not necessarily entail a delayed hulhangu. The wet season depends on the cooler oscillation of the Pacific Ocean.

“It is now in La Nina, and is expected to continue into March and April. If that is the case, there is a chance of the southwest monsoon being delayed,” Shabin said. “But it’s more of a waiting game to see what happens.”

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.