When the gallery went dark, the light began to dance

Dhona's exhibition was the first spatial light installation.

05 Jul 2025, 14:08

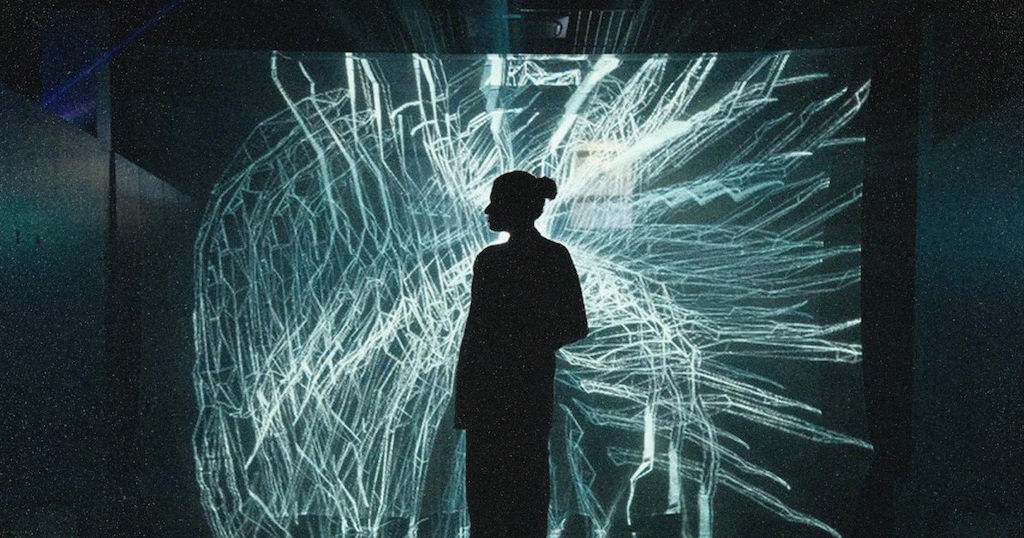

The National Art Gallery went dark for the first time. Visitors stepped into unfamiliar territory on that warm June evening, finding the brightly lit space they expected transformed into pulsing geometry and shifting beams of the light.

The artist who made the light dance was Aminath Sultana, better known as Dhona. After more than a decade living and working in the UK, she returned home to present her debut solo exhibition 'Ali' (meaning light in Dhivehi) from June 21 to 26, marking the national gallery’s first spatial light installation.

The exhibition opened with a close-knit gathering of family members and friends from creative disciplines. The static backdrop of the stark white gallery walls served as canvases for light, shadow, and movement.

Dhona sculpted an ephemeral architecture of photons, using laser beams, shadow, and particle interaction. Responding to sound and movement, the installation shifted and unfolded in real time, creating a sensory experience rooted in light and geometry. The installation was divided into two sections. On one side, beams of light reflected and shifted in colour. At the center of the gallery, the conceptual heart of the piece featured a 10-minute projection cycle of morphing geometric shapes.

"I didn't know what to expect from the audience," says Dhona. "That was kind of the point. No one's really done something like this in the gallery before. Most people only associate these kinds of projections with nightclubs or stage lighting. I wanted to bring that language into the gallery space, without giving away too much in advance. The idea was to let curiosity guide the experience, and to learn from how people respond."

Sitting on one of the wooden benches positioned in front of the central projection, I found myself absorbed by the rhythmic, shifting light forms. Some danced like water ripples under the hot sun, flickering under a turquoise lagoon. Others morphed into bird-like silhouettes, reminding me of the white dhondheeni seabird. At one point, a flurry of micro-particles spun across the space, as though inviting us into the artist's earliest memories of playing in light beams.

Dhona's fascination with light stretches back to her childhood. "When I was a kid, we had this entrance hallway in our home," she recalls. "The tiny holes left by nails in the roof would cast these narrow beams of light into the house. I used to play with them like toys. I would spend hours on the rooftop just watching how light behaved. That curiosity stayed with me."

Though she began her career in journalism, managing websites and digital content, Dhona was soon drawn toward visual experimentation.

"I started looking for software that could control light," she says. "I came across an artist's blog that shared open-source patches for installations. I learned from that and slowly began creating my own."

Over the years, Dhona has collaborated with renowned artists and creative teams in London, crafting immersive visuals through laser mapping, production design, and data-driven art. Most recently, her laser performance was featured at the Digital Awards Show hosted by the House of Fine Arts in collaboration with the Philips Gallery in Mayfair.

"Some of the techniques used in this installation aren't new, in London or other parts of the world," Dhona explains. "Even I've worked with them before in different settings and exhibitions. But I felt it was important to bring something like this to the Maldives. I thought it would be meaningful to present it here."

Her current installation is "like a portal in the centre of the room," an experience meant to draw visitors into her world, shaped by memory, imagination, and technical skill. It's also deeply personal, offering glimpses into the light-filled wonder of her childhood.

There's something moving about how a moment of innocent fascination in early life can manifest into a full-fledged art form. Dhona's Ali is a testament to that journey, showing how the questions and curiosities we carry as children can evolve into immersive works of art when nurtured over time.

One of the youngest mediums in contemporary art, light art first gained prominence in the late 1960s through pioneers like Robert Irwin and James Turrell. Its belated arrival in the Maldives is worthy of celebration.

Yet it's hard to ignore the challenges. The country's National Art Gallery operates with limited support. The culture ministry has historically placed the arts low on its list of priorities. Infrastructure is minimal and local artists often find themselves navigating a system that offers little institutional encouragement.

Despite these constraints, creatives like Dhona continue to forge their own paths rooted in vision, resilience, and a desire to contribute something meaningful to the cultural landscape. In this sense, Ali arrives not only as an art installation but as a quiet declaration: of potential, of homecoming, and of light in unexpected places.

As the art curator and film director Aaron Rose put it: "In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary."

Perhaps the timing couldn't be more right.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.