The artist as test-subject: the life and work of Mohamed Ikram/Araakaa

Mohamed Ikram’s journey from tourist art to protest ink captures a life shaped by music, politics, and the streets of Male’.

Artwork: Mohamed Ikram/Araakaa

10 May 2025, 17:40

In the 1980s, Mohamed Ikram (Ika/Araakaa) was a young boy in a household caught up in the boom of tourist art. To Ika, art was a colourful parrotfish or the stretch of sand beside the blue-green sea of an island idyll. His father printed T-shirts for his souvenir shop using the Indonesian batik print technique that was favoured throughout the 80s and 90s, and young Ika would sometimes try his hand at printing.

“I learned quite a bit from my Dad,” recalls Ika. “Like freehand lettering for signage (there was no computer at the time) and a lot of stencil work on paper and stickers. Even the T-shirts are all hand-drawn and turned into stencils for printing.”

During the ’86 World Cup Ika was in primary school, where he bonded with one of his classmates who came from a similar household.

“My friend and I were completely captivated by the World Cup, and we loved the logo,” recalls Ika. “Sometimes, I’d bring printing material from home to class – some dye, and a bit of sponge, and he’d do the same. We’d copy World Cup graphics, the stuff we saw in newspapers, make stencils and print in the classroom.”

This was the first football World Cup aired in the Maldives, a time when the Argentinian legend Diego Maradona stole the hearts of youth everywhere with his mesmerising skill as he led his nation to football glory. It was also Ika’s first encounter with the power of graphic design, and the start of a life-long love affair with the beautiful game.

The power of sleeves

Besides the odd ‘mauraz’ or exhibition, highly curated by former president Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, Ika does not remember any art events in the city while he grew up. An art community was non-existent, and as a means of free expression, art was sometimes viewed with suspicion. Ika’s movement beyond the work intended for the tourist’s gaze came from an unlikely source: music.

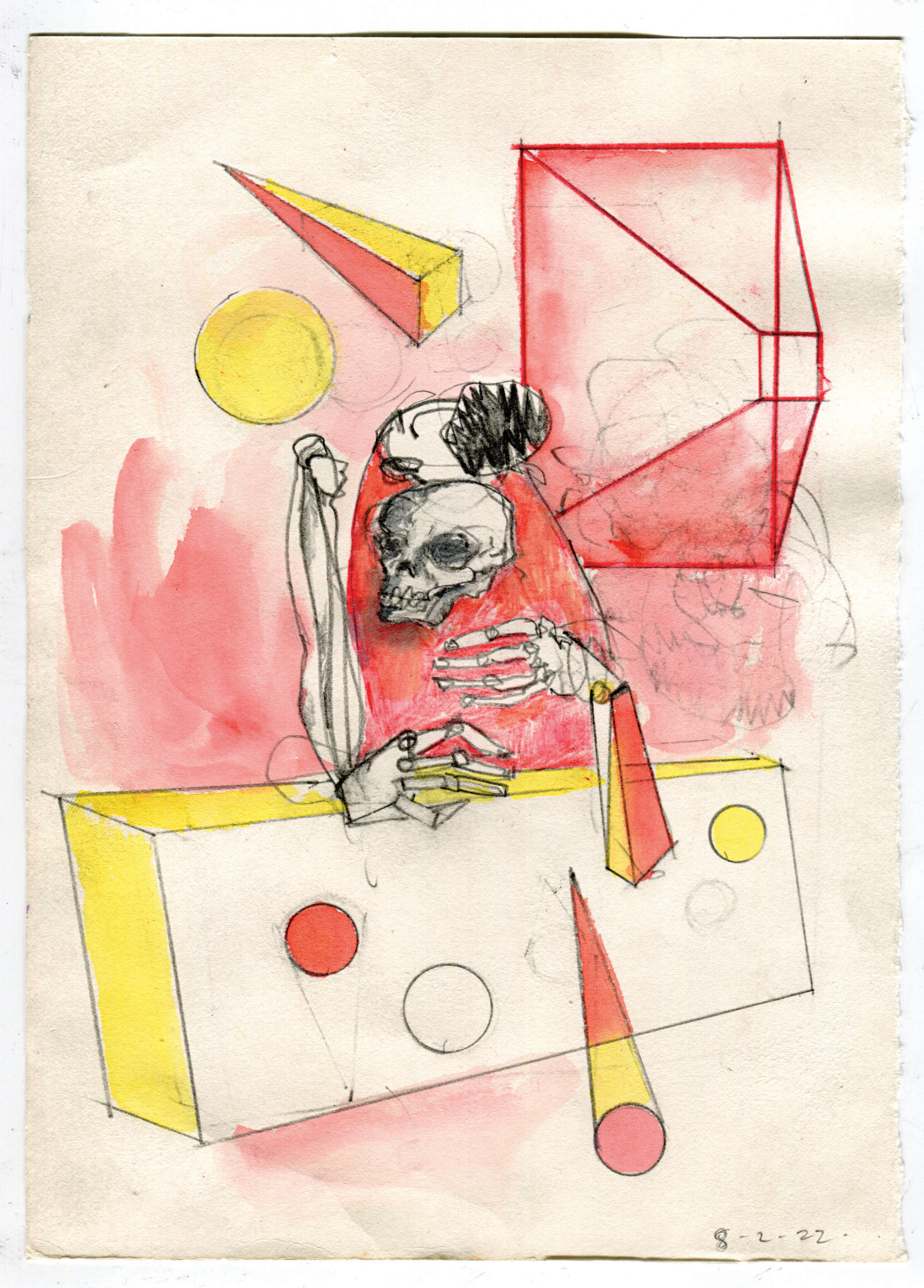

“I loved the covers of Iron Maiden, their mascot Eddie the Head was fearsome and instantly recognisable,” he explains. “It opened my eyes to the possibilities of art.”

Megadeth was another favourite of the time – the smiling skull of their recurring mascot Vic Rattlehead was diligently studied and copied many times over by the young artist.

The music found its way to Ika through his older brother. In the mid-90s, Ika started hanging around Masterpiece, a hub of local talent that turned into a hang out spot. There, he spent time in the studio, making friends and discovering the Seattle grunge scene. He became familiar with the sound and art of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains.

“What really blew everything else out of the water for me were the CD sleeves of Pearl Jam,” says Ika. “They were so painstakingly designed. Ten was a folded-up poster with a great font. Vitology was like an old book. No Code gave us a bunch of fascinating Polaroids.”

These showed Ika what art was capable of, especially from a design perspective. Later, things levelled up with the CD sleeves of Radiohead’s OK Computer and Kid A as well as REM’s Up. Ika was exposed to the art of Stanley Donwood, who remains a major inspiration to this day.

Meanwhile, at the studio, people brought over music magazines like Spin, Q and Kerrang!. Ika became enamoured of the artistry of their typefaces, graphics, and use of space on the page. So began a long romance with design.

What do the signs say?

Almost immediately after school, Ika started working for his brother designing signage, and he applied what he had picked up from observing magazines.

There was a sudden twist of fate, however, when Ika was conscripted to military service around the mid ‘90s.

“I was put in the project office, in their architectural department,” he says. “I was working with Filipinos, as there were no qualified locals in the military at the time. The head engineer was from the Philippines, as were the architects and site engineer.”

Soon-to-be local military architects were abroad learning the trade, so Ika had access to skilled foreign tradesmen at the infamous Kalhuthukkalaa Koshi, near Male’s North Harbour.

He learned how to produce drawings manually from the chief architect, using specialised tools like the mechanical ruler. Ika believes he developed something of a style from studying his boss.

“They had a style of drawing when they rendered buildings, trees. No two architects would draw the trees the same, you know? They all had their own style. It’s something of a lost skill now, when things are rendered on the computer.”

Becoming himself in the early 2000s

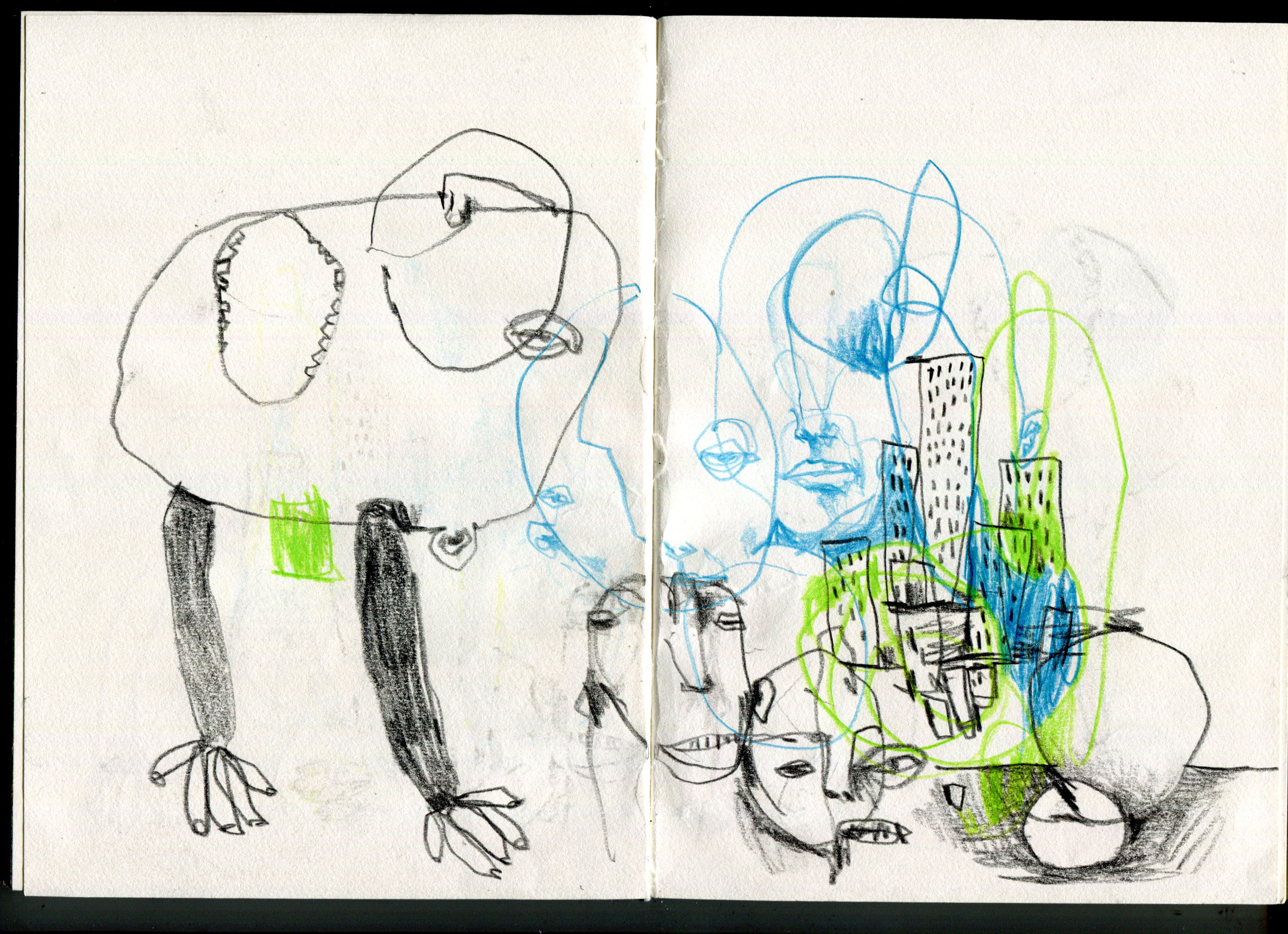

Armed with lessons from NSS, Ika began the 00s with a fresh eye and a healthy dose of optimism. This was a defining period of his artistic life. Revolution was in the air, and he started work in earnest as a graphic designer with the young crew at Masterpiece. Ika dived into cityscapes in his art, and like Godard with Paris, Male was his muse.

Politically, Male was a pressure cooker – Maumoon’s repressive regime was in its death throes. Evan Naseem’s death in prison at the hands of his torturers shook the entire nation. Ika, who was an art stream student in secondary school, never had problems connecting the dots – it was obvious to him that Maumoon was at the very least an autocrat. Like many Male-based households, Ika’s never looked up to Maumoon - although they did not advertise this.

Around this time, Ika lucked out and got an opportunity to study film production at a college abroad.

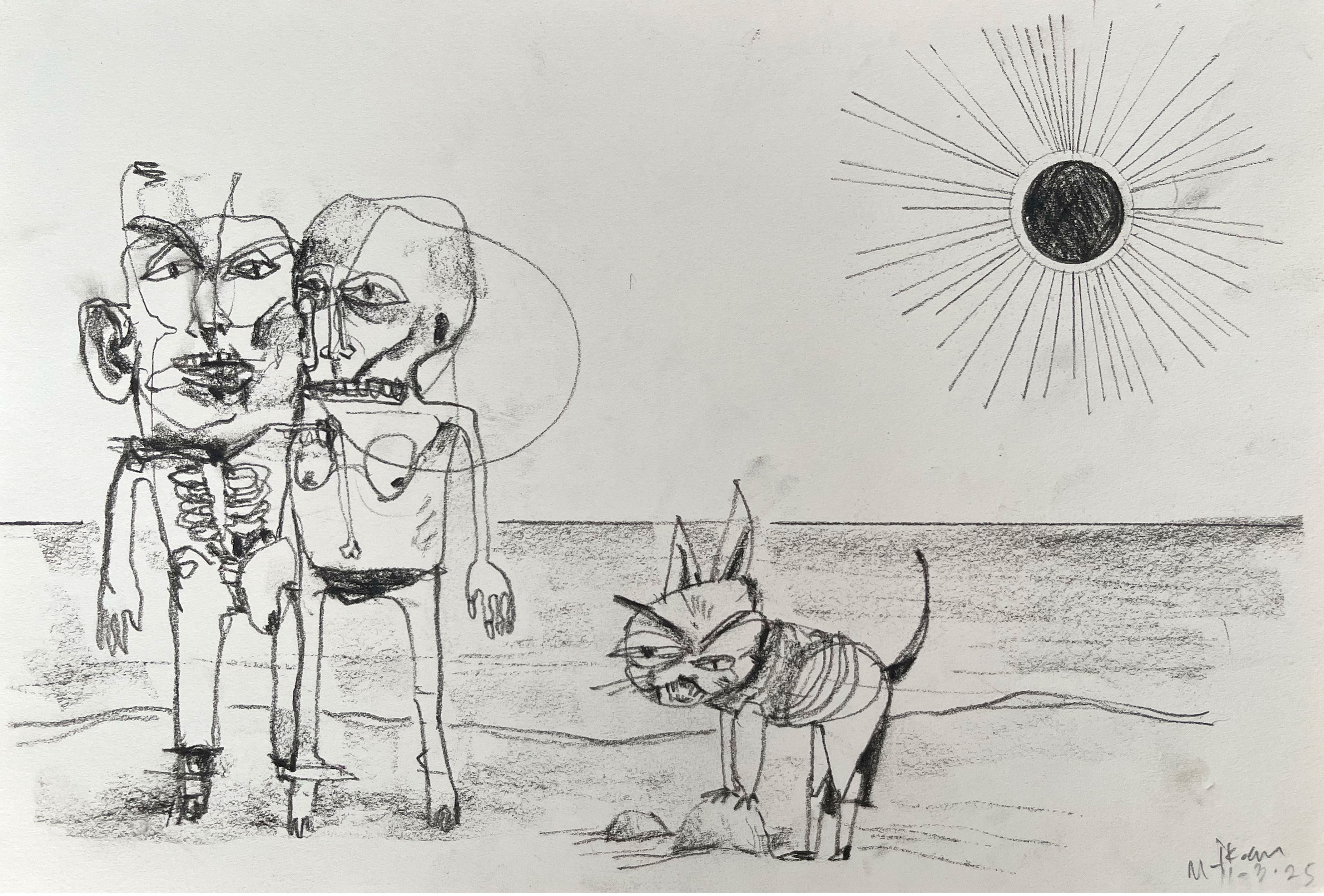

“What fascinated me was the life drawing classes,” he says. “That’s how I was introduced to sketching figures with charcoal.”

Ika was also drawn to human anatomy and became familiar with depicting figures in different poses. He spent several hours a day familiarising himself with the human body through his drawings, and any fan of @araakaa’s art will see the effects of this in his work. He also became acquainted with the works of key artists who were to have a lasting influence on his work including the seminal Ralph Steadman who illustrated the “journals” of Hunter S. Thompson, and Saul Bass, whose minimalism attracted the attention of Alfred Hitchcock.

#mvcoup era and first exhibition

Back home in Male, Ika took design even more seriously. Soon, though, he was carried away with the euphoria of the 2008 election. Change was in the air, and under the guiding hand of Mamduh Waheed (Dommu), new forms of art were being exhibited at the National Art Gallery.

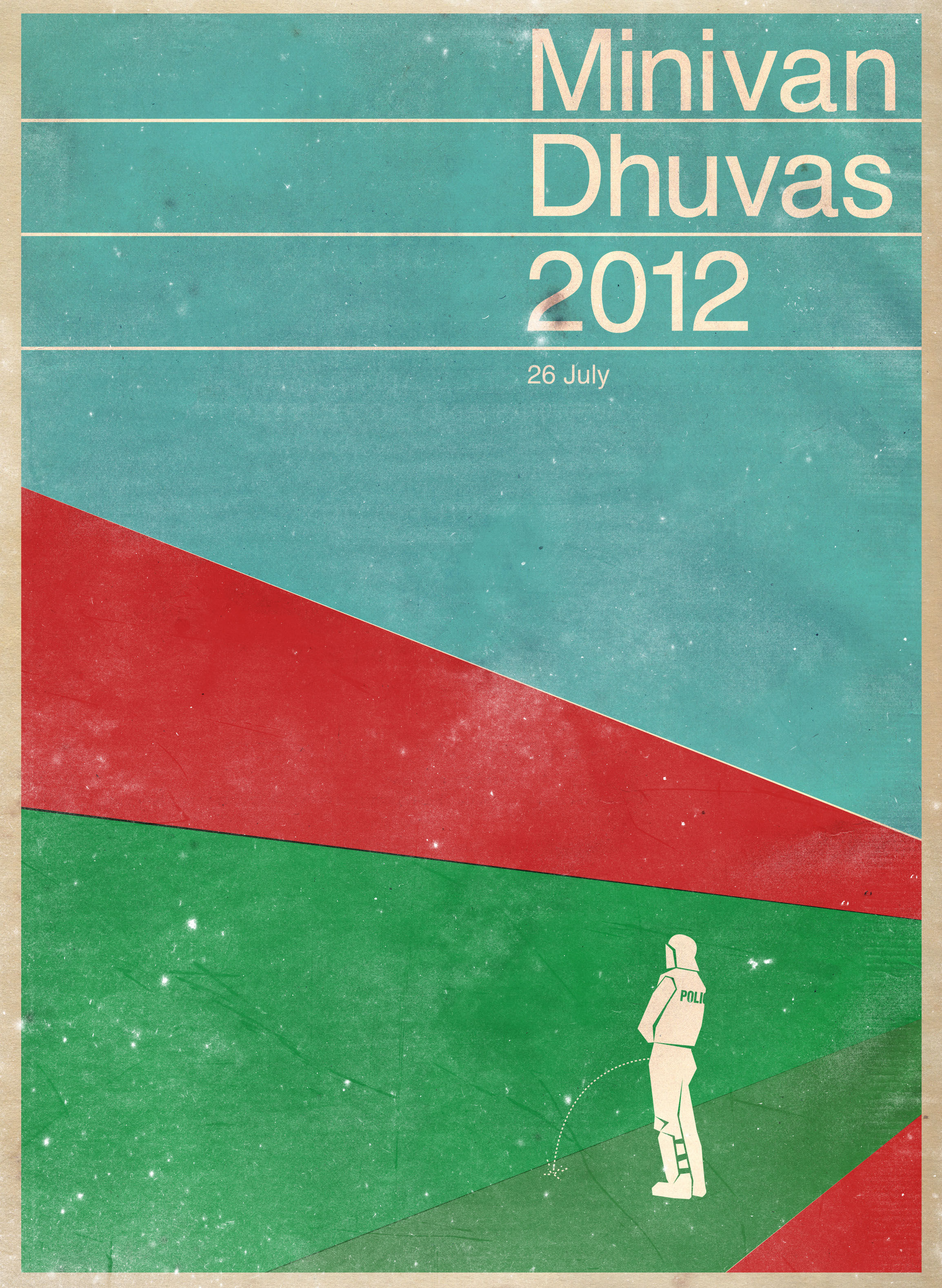

The fall of the first democratically elected government in 2012 brought Ika and many other artists together in a period of frenzied expression. The coup de état created a rift with lingering effects to this day.

Ika’s socially conscious work during this period captured the attention of thousands – it was my first encounter with his art as well. I had long heard of an artist with prodigious skill called Ika (whom I had thought Japanese at the time) who worked at Masterpiece some years ago. Two pieces from this time stand out to me: one is a special-operations (colloquially dubbed “Golhaa force”) cop urinating on the Maldives flag, his arc of pee forming the crescent. The other is a starker, darker, image: a woodcut-like graphic of a drooping blossom that has grown from a police boot, shedding its petals.

Waheed’s presidency being given legitimacy, and the murder of the moderate religious scholar Dr Afraasheem Ali, gave Ika pause, and he was ensnared in the culture of fear. Like many others at the time, the artist went into retreat.

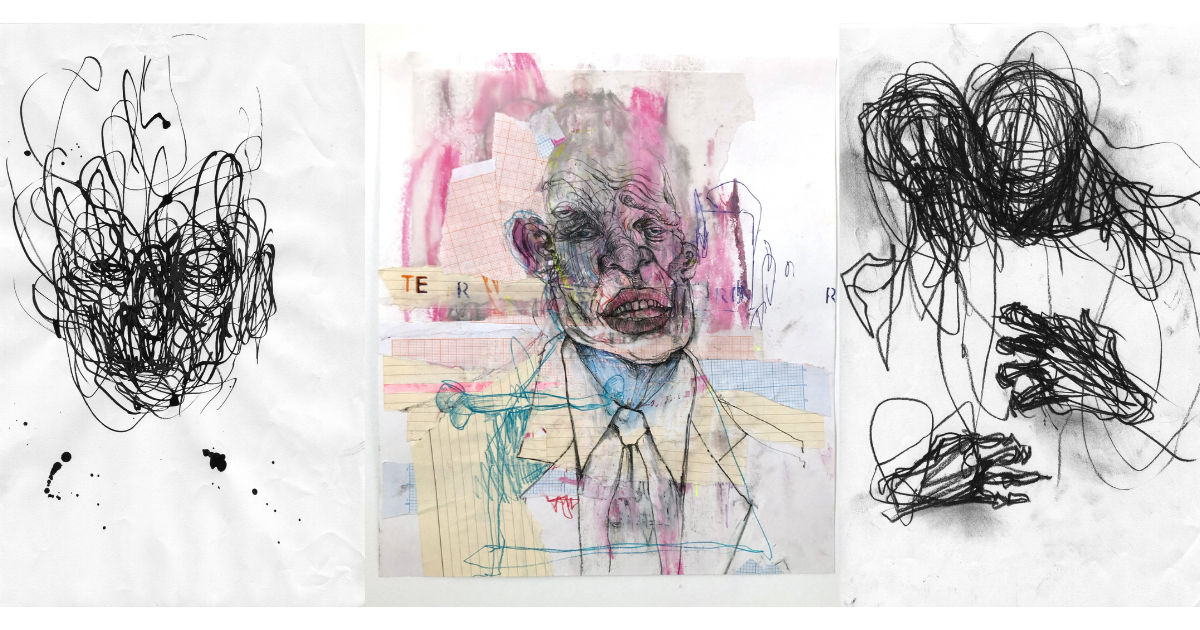

However, Ika resurfaced in 2016, wishing to make something of his recent explorations with ink. It was a series borne from a month-long journey inward that was given form by the artist, curator, and freediver Umair Badeeu. The exhibition took place at Ika’s home, which added a layer of intimacy to the already personal subject-matter. It left Ika feeling exhilarated, and perhaps more importantly, it finally gifted him with a sense of accomplishment.

Blinkers off – Silence and Noise – Ika’s sophomore exhibitions

Three years later, in 2019, Ika exhibited again under Blinkers Off at the now-closed Avatteri Gallery in Hulhumale.

This time, Ika was exploring relationships and societal decay, influenced by the work of print maker Kathe Kollwitz and photojournalists dealing with similar subject matter.

He was interested in capturing a feeling, in its evocations in art. So, the canvases were dark, sometimes nightmarish, and you clearly got the sense that things were frighteningly awry.

“It is a conversation about societal decay, as a subject, but it was also talking about us, too,” explains Ika.

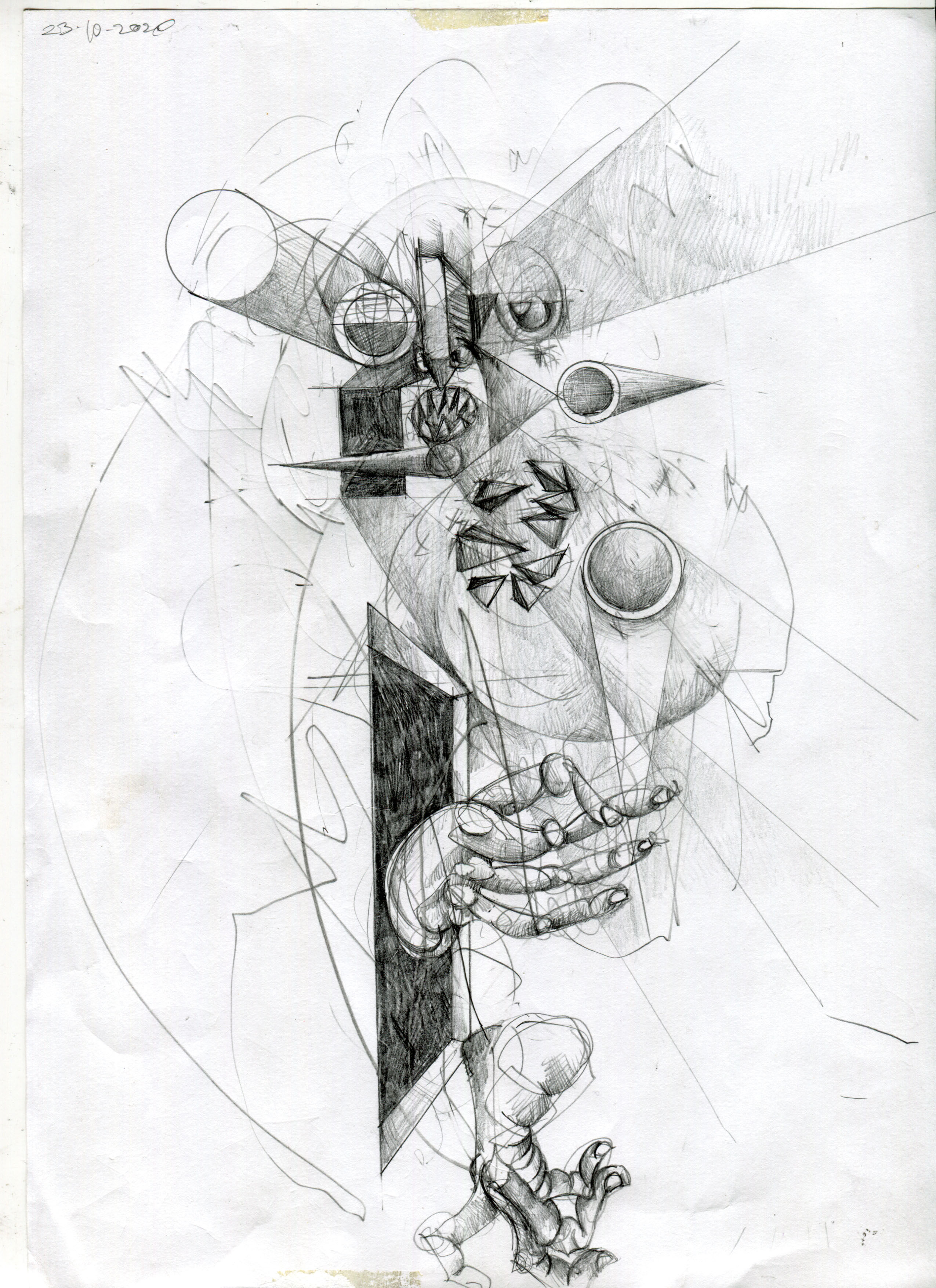

A year later, COVID-19 happened. As with many others, it proved to be a tumultuous period in the artist’s life.

“I spent a lot of time figuring things out back then,” Ika recalls. “But I was also very focused on my art, and I was very disciplined.”

The new exhibition, Silence and Noise, showed Ika adding more elements to his work, including geometry that recalled Wassily Kandinsky.

“It was three years of work, and mostly about trying to find a balance within the yin and yang we all carry,” says Ika.

It included some of his most “free” pieces where the artist seemed to have got in touch with a deeper self and completely let go.

Now, we stand on top of a building, looking over at the Tetris-like structures and rooftops of Maafannu, Male – a subject that still inspires Ika. Our little island city is full of people, stories, images, sounds, and ideas that can elevate those who’re receptive to rarefied heights and frightening depths. It will hopefully inspire the coming generation of artists just as it did @araakaa, a generation that seems fearless and thirsty for the next revolution. And in the meantime, I hope it will find community and care in the confines of this city we call home.

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.