In chains: human rights in the Maldives

Praise for human rights progress in the Maldives has angered and alarmed defenders.

12 Dec 2017, 9:00 AM

Last Sunday the Human Rights Commission of the Maldives celebrated the “great successes in the areas of protecting, promoting and sustaining human rights” in the country.

The statement, marking Human Rights Day, lamented how “harassment, mockery, defamation and hateful acts have increased and acts that are harmful to a person’s life have also increased.” Such acts were, it said, against the norms of the “historically Islamic tradition of respect practiced in Maldives.”

Their assessment – and their assertion that there needed to be limits to freedom of expression – have alarmed and angered human rights defenders.

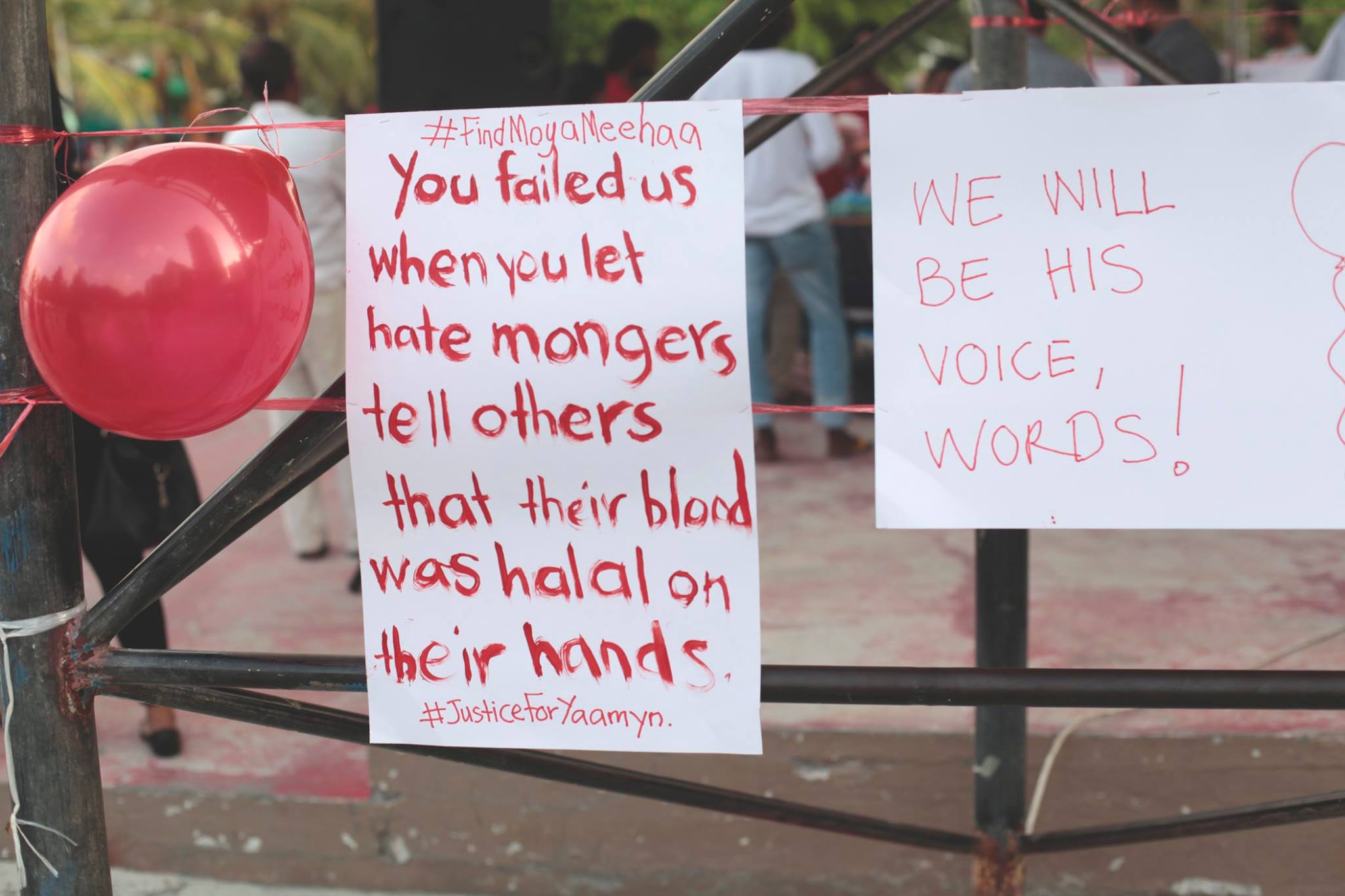

“We are all in chains,” says Aishath Rasheed. Her brother, liberal blogger Yameen Rasheed, was brutally murdered in April. His death was followed by threats of more killings. Yameen had been campaigning to find his friend and abducted journalist Ahmed Rilwan, who disappeared more than three years ago. Police have used social media to issue summons for liberal bloggers living abroad for unspecified allegations. Freedom of expression has been curtailed by a defamation law.

Become a member

Get full access to our archive and personalise your experience.

Already a member?

Discussion

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!

No comments yet. Be the first to join the conversation!

Join the Conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts under an alias and take part in the discussion. Independent journalism thrives on open, respectful debate — your voice matters.